For the 125th anniversary of women gaining the vote in New Zealand, it pays to look back on how things have changed - not just in the static moments between then and now, but in the gradual shifts over intervening decades ...

One generation after suffrage day

It might not have happened, except that the vicar at St James' Anglican Church in Lower Hutt had a very forward wife.

The year was 1954, 61 years after women had won the vote, but sometimes it was hard to tell that they had won much at all. Women could not go to the bank without a man there for security. She could not seek a home loan without a male guarantor.

And it was difficult to know where to turn if you wanted to change things; women's organisations existed largely as chapters within either the Christian church or farmers' groups. They were permitted an interest in two topics: health and education.

Dame Miriam Dell with her granddaughter, Willa Dell. Photo: Supplied / Sharon Dell

Miriam Dell, then 30, says the Mother's Union at her local church were "all middle-aged or elderly ladies" and there was nothing for young women like her.

"There was no particular way of listening to us," she says, "so a few of us kicked up a bit of a fuss about that."

Back in 1940, while a 16-year-old university student of botany, Miriam had been barred from speaking at the campus science club because she was a woman.

"When I got up to speak, they said, ‘you're not here to speak, you're here to make the tea'," says Miriam, who is now Dame Miriam, 94. "Of course, that probably is what propelled me into the way I've gone."

She went back to the science club later, prepared with what she wanted to say, and said it. So began the advocacy career of a woman who would go on to become one of the past century's greatest campaigners for women's rights in New Zealand, fronting up to government ministers to petition for women’s representation in New Zealand’s laws.

But before all that came the vicar of St James' Anglican and his "very forward wife". That wife began a group, which Dame Miriam promptly joined, that would eventually spread to chapters in churches throughout New Zealand as the Association of Anglican Women.

It was an organisation for young, married women that "grew madly", Miriam says, and would serve as an incubator for decades of her future activism.

“I was always very keen for women to take their place in the wider world, not just to be at home,” says Dame Miriam, who did not leave her job as a science teacher once she married, as was customary at the time.

Instead, she says her supportive husband hired a weekly cleaner to help with the housework so Dame Miriam could continue to work, attend women’s meetings - which took her throughout New Zealand and later, around the world - and raise four daughters.

The hard work paid off, with Miriam eventually gaining audiences with government ministers, instead of being brushed off, she says, with mere heads of department.

“The first one I went to see was the Minister of Agriculture, and he was a nice man, I must say, but he was so condescending about what we had to say that it rather sharpened me up,” Dame Miriam says. “It made me much more aggressive.”

At one point calling herself “New Zealand’s token woman”, Dame Miriam sat on every committee and board who asked for her, often as the only representation of her gender. She went on to lead the International Council of Women.

Speaking of “hair-raising” experiences early in her gender equality work, she said she had shared elevators with people "who didn’t think we had a place in public life".

But it was no good being too solemn and earnest, she said, or getting offside with those you wanted to influence. A sense of humour was required, and squeamishness to be avoided.

Some of Dame Miriam’s family had grown up in a time when they would not have been allowed to vote, but they never spoke about it. She just has one letter, written by a relative, that recounts going to cast her ballot for the first time. The woman said she "rejoiced".

Two generations after suffrage day

Miriam Dell told her four daughters they could be whatever they liked, but women in the 1970s were discovering that wasn’t always true.

Sandra Coney, now 73, was one of those women. She wanted to attend law school, but the university told her that as a mother, it wouldn’t be appropriate.

Sandra Coney Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

Ms Coney took anthropology instead of law, founding New Zealand’s first campus creche in the process. She went on to generate a wealth of feminist books and journalism, and to help secure healthcare, including abortions, for women who could not access them.

But as a young housewife, the fledgling women’s equality movement had almost passed Ms Coney by.

She "distinctly remembered" telling an activist who urged her to join the movement that she “didn’t need to do that because I'd got a very nice husband", she says.

Concerned about the lot of other, less fortunate women, she attended her first meeting. There, a consciousness-raising programme which called for the women to discuss topics including their bodies and family dynamics acted as a wake-up call for Ms Coney.

If she believed there were no curbs to her freedom as a young New Zealand woman, why had she and her peers been pushed towards nursing or teaching once they finished high school? And why did girls who wanted to study science have to visit the boys’ school up the road?

“You were definitely being groomed for a particular role in life, even though you were there at the school with these quite powerful women who ran the place,” Ms Coney says.

Having married and given birth to her first child at 18, she found herself a single mother in the early 1970s; single parents did not receive social welfare benefits, and Ms Coney heard of women who slept with their employers for food and a roof over their heads.

Stigma and judgment was rife. And the law school, with its evening lectures - structured around men’s work hours - wasn’t interested in taking Ms Coney on.

"They sort of said you have to choose between motherhood and higher education,” she says, “and I thought, damn it, I'm going to do both."

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

She juggled several jobs, including one as editor of the influential women’s publication, Broadsheet, and another as counsellor and advocate for women seeking abortions and reproductive healthcare. The clinic she worked at was raided by police, picketed, and on one memorable occasion, set on fire, but she felt New Zealanders were on the women’s side.

“People thought it was unreasonable that women would have to go to Australia for an abortion,” she says, referring to her work assisting women in making the trip, during a period when abortions were not accessible in Auckland at all.

Despite her achievements, Ms Coney struggled to name one she was proud of, worried by how much further women had to go. A gender disproportionately affected by low wages and domestic violence, she says. “Neoliberal economic theory” had “pushed women further and further down”.

In 2018, Ms Coney would be happily accepted at law school, but the past year’s stories of sexual harassment at top-tier firms shows that the legal sector must still work harder to make women feel welcome there.

“I think it’s been good to expose that sexist oppression. It is systemic,” she says of the scandals.

There are plenty of barriers to gender equality remaining, even for “high flying women,” she says, “but at least they’re bringing home a fair wage". Many, she said, were not so lucky.

Three generations after women's suffrage

For Mera Lee-Penehira, now 49, it began with a pounamu, and a warning from her father. Growing up Māori in the 1970s and '80s meant being “born into a battlefield”, she says.

Dr Mera Lee-Penehira Photo: Supplied / Qiane Matata-Sipu

Among her earliest recollections is the memory, age 14, of defending a friend who’d had her greenstone taonga taken from her by teachers at school, because of a strict no-jewellery policy.

“I remember the absolute distress that that caused her,” Dr Lee-Penehira says. She succeeded in having her classmate’s pounamu returned to her at the end of the day and when she told her parents the story, they were both celebratory and cautious.

“They were scared that I might face retribution,” she says. “I remember my father saying to me: ‘Be careful what you know. Be careful what you learn. Because sometimes the more you know, the harder your life will be'.”

At 14, she already understood that as a Māori teenager her very existence was political. Her father’s words galvanised her to face it head-on.

Dr Lee-Penehira, who has worked for decades in Māori education, became part of the Māori sovereignty movement at university, through membership of campus groups and unions. But the suffrage movement never felt like hers.

“Gender equality for young Māori women has a very different history to gender equality for other women,” she says.

“The suffrage celebrations are not really a celebration for us. Unless you delve a little bit deeper, it can look like there was equity there, but there wasn't really.”

While all New Zealand women received the vote in 1893, Dr. Lee-Penehira said, most Māori women were excluded from casting a ballot, because of other laws.

“If you didn't own your own land, you were precluded from voting. Most Māori at that time, in the 19th century, lived in papakāinga, or collective land,” she says, adding that even if they were able to vote, Māori were only permitted to cast their ballot for Māori seats until 1975.

Participating in the movement had taken a toll on wāhine Māori, she says; women had to make a pledge before joining the Temperance Union that they would not imbibe alcohol, smoke tobacco, or take the Māori chin tattoo - moko kauae - that had formed a traditional part of their cultural identity.

Dr Lee-Penehira says the Māori immersion schooling system was one place young Māori women could learn about the politics surrounding their existence. Her daughter, who attends one, is 14, the same age her mother went to petition for her schoolfriend's pounamu.

“I think my biggest contribution to the wāhine Māori movement is raising a daughter who speaks Māori as her first language,” she said.

“I do think it's important that we reclaim and retell the history of women's suffrage, from a Māori woman's point of view.”

* Charlotte Graham-McLay is a New Zealand freelance journalist who has worked for RNZ, the New York Times and others.

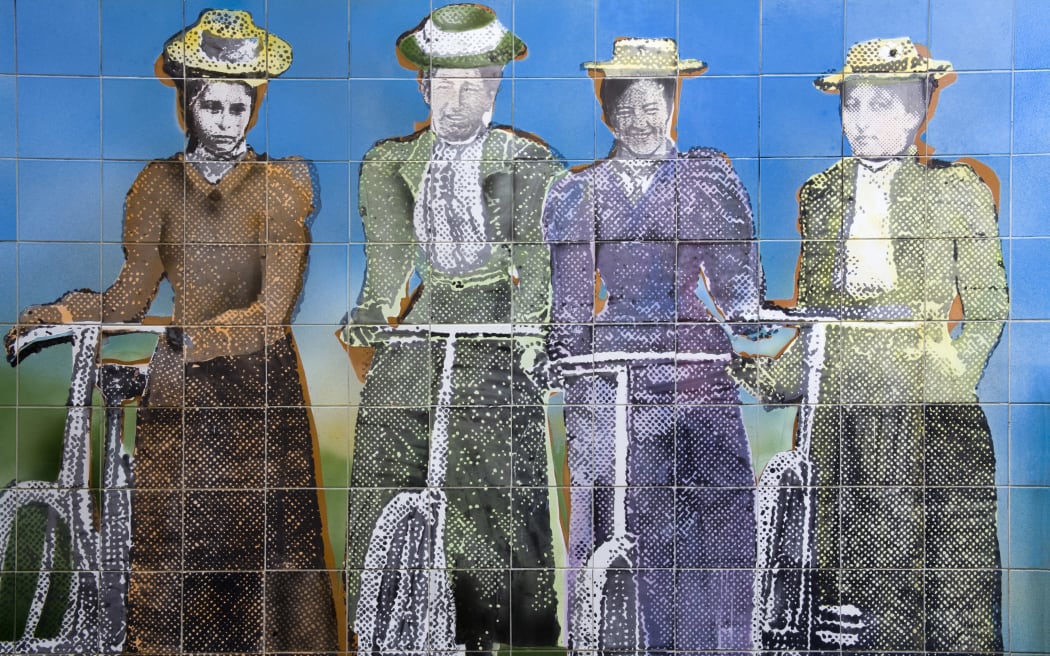

This photograph comes from an album created by the North Shore Womens Suffrage Centennial Co-ordinating Committee. It was taken on 19 September, 1993, exactly 100 years since the right to vote was extended to women. Photo: Jock Phillips / Te Ara / Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga