If you are looking for an introduction to the work of the Danish master, Carl Th. Dreyer, his final film probably isn’t the best place to start, says Dan Slevin.

Poet Lidman (Ebbe Rode) and unfulfilled housewife Gertrud (Nina Pens Rode) contemplate what might have been in Gertrud (1964) Photo: Criterion

#43= Gertrud (1964)

Danish master Carl Th. Dreyer has a remarkable three films in the Sight & Sound Critics’ Top 50 of all time – the same as Alfred Hitchcock and Martin Scorsese put together – but before Gertrud I’d never seen any of his films. And now that I have, I’m wondering what those critics were smoking!

Gertrud was Dreyer’s final film, released in 1964, nine years after Ordet won the Golden Lion at Venice and 36 years after The Passion of Joan of Arc reinvented cinema in 1928 (all three are in the Sight & Sound Top 50). It’s a shame that I am counting down from 50 in this project because it means I’m watching Dreyer’s films in the wrong order.

Gertrud feels like the work of a tired old man. It is wistful and regretful. It is also slow, as if Dreyer is struggling to get out of his chair to make a cup of tea. Based on a 1906 stage play by Hjalmar Söderberg, it is the very Nordic story of a passionate woman trapped in a loveless marriage and punished for choosing to love the wrong man.

Gertrud (Nina Pens Rode) is a former opera singer with what might be a scandalous past but who is now married to establishment figure Kanning (Bendt Rothe). On the day he announces he is to become a government minister she tells him that she is unhappy and intends to leave him. It turns out she has already commenced an affair with talented but feckless composer Erland Jansson (Baard Owe).

Nina Pens Rode characteristically staring into space as Gertrud and Bendt Rothe as her husband Kanning in Dreyer’s Gertrud. Photo: TCM

To complicate matters, a former lover, the great poet Gabriel Lidman (Ebbe Rode) is in town to receive an award. The night culminates with both Lidman and Kanning failing to woo her and Jansson proving to be utterly unworthy of her.

I’m looking forward to discovering that Gertrud is atypical of Dreyer’s other work – he himself described it as an experiment in prioritising dialogue over image. Reportedly, it took three months to shoot but only three days to edit because each scene was effectively one long take. But the lack of drama and tension in the scenes themselves makes me wonder whether this film would have the reputation it does if it wasn’t from one of the masters.

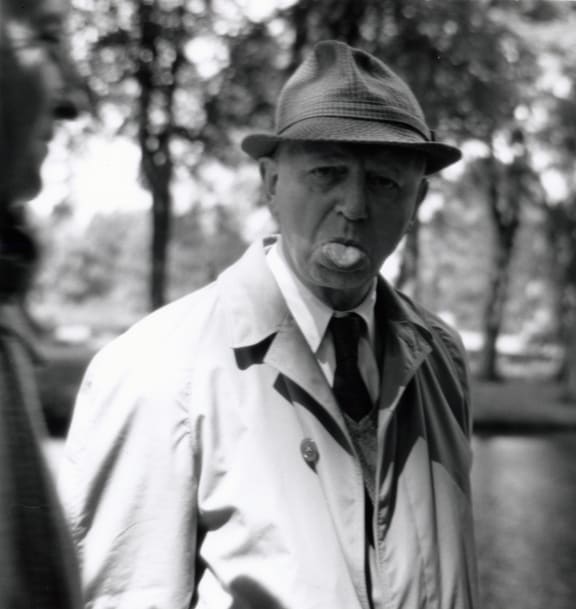

The Danish master, Carl Th. Dreyer, on location for Gertrud (1964). Official caption: “While shooting Gertrud, the photographer Else Kjær followed Dreyer closely. The image above shows Dreyer in a rather atypical expression.” Photo: Danish Film Institute

Stagy to a fault, with little direct eye contact between the players, Pens Rode, in particular, spends so much time staring off into space that I thought she was reading the dialogue off the back wall of the studio.

It comes as little surprise to me to find out that the film was booed at its premiere in Denmark but I’m equally unsurprised to learn that great cinematic practical joker Jean-Luc Godard named it film of the year in 1964.

In all honesty, I can’t recommend it to anyone other than film scholars and sad completists like me, but if your interest has been piqued, you’ll find a DVD (letterboxed in 4:3 ratio) available at fine video rental stores but it’s not on any local streaming or download services and nor is there a high definition Blu-ray available like they have through Criterion in the USA. That would look quite fetching, I imagine, as the black and white photography is one the film’s few pleasures.

The Sight & Sound Top 50 project is intended to encourage more attention to the greatest films of the past – in the same way we still read old books and listen to old music we should be appreciating old movies.