A woman who was jailed for life for ordering the murder of a West Auckland man wants her case to be one of the first to be heard by a new government tribunal which will examine suspected historic miscarriages of justice.

Gail Maney has spent 15 years behind bars, and is currently serving out a life sentence on parole for the murder of Deane Fuller-Sandys.

In the true crime podcast series Gone Fishing - a joint production between Stuff and RNZ - she maintains her innocence and said her story hasn't changed since being arrested in 1997.

Maney said she was confident that the Criminal Cases Review Commission would be able to pick apart the flaws in the case against her. She has also applied to the New Zealand Innocence Project, and most recently, to the New Zealand Public Interest Project - groups manned by experienced investigators, lawyers and scientists who volunteer their time to investigate potential miscarriages of justice.

The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) is due to be set up by the Labour-led Government by mid-2019. It was part of a coalition agreement with NZ First in response to an ever-growing number of cases where people have claimed they've been wrongfully convicted.

In the past 20 years, seven payouts totalling $5.3 million have been made to people who have been wrongly convicted. Most recently, Teina Pora was awarded $2.5m for spending 21 years in prison.

Maney was found guilty of ordering the killing of Deane Fuller-Sandys, who went missing in 1989. At the time it was thought he had slipped from rocks while fishing on Whatipu, a beach on Auckland's dangerous West Coast.

Maney and three others were arrested, including Stephen Stone, who carried out the hit, as well as Mark Henriksen and Colin Maney who got rid of Fuller-Sandys' body. They were all found guilty at their first High Court trial at Auckland in 1999.

Gail Maney. Photo: Jason Dorday / Stuff

But Maney launched a successful appeal, which quashed her convictions and a retrial was ordered. However, she was again found guilty by a jury a year later. A second appeal was thrown out.

In Gone Fishing, Maney said she did not know the victim, and that no murder ever took place at her home. She added that there was no evidence to link her to the crime either - luminol testing could not detect any traces of blood on the garage floor where he was meant to have been shot, and ballistics experts could not detect any markings from bullets.

Tim McKinnel, a private investigator who helped set up the New Zealand Public Interest Project (NZPIP), could not speak in detail about Maney's case but said that on the face of it, there were several red flags, mainly, the lack of evidence.

"Based on my limited knowledge, there are issues around reliability of witnesses ... but importantly, there doesn't appear to be any corroborating forensic evidence and when there isn't corroborating forensic evidence it means you're left relying on human witnesses and we all know how fallible humans can be," he said.

McKinnel said a recent example of a jailhouse witness prosecuted for perjury was an example of "risky testimony" that makes its way in front of juries.

"There is a growing scientific and psychological evidence around memory, around identification, our ability to detect lies and a jury or court's ability to detect lies based on evidence. So as that side of science develops we are starting to question the way that evidence is produced and I think there is a growing need for corroboration in these criminal cases.

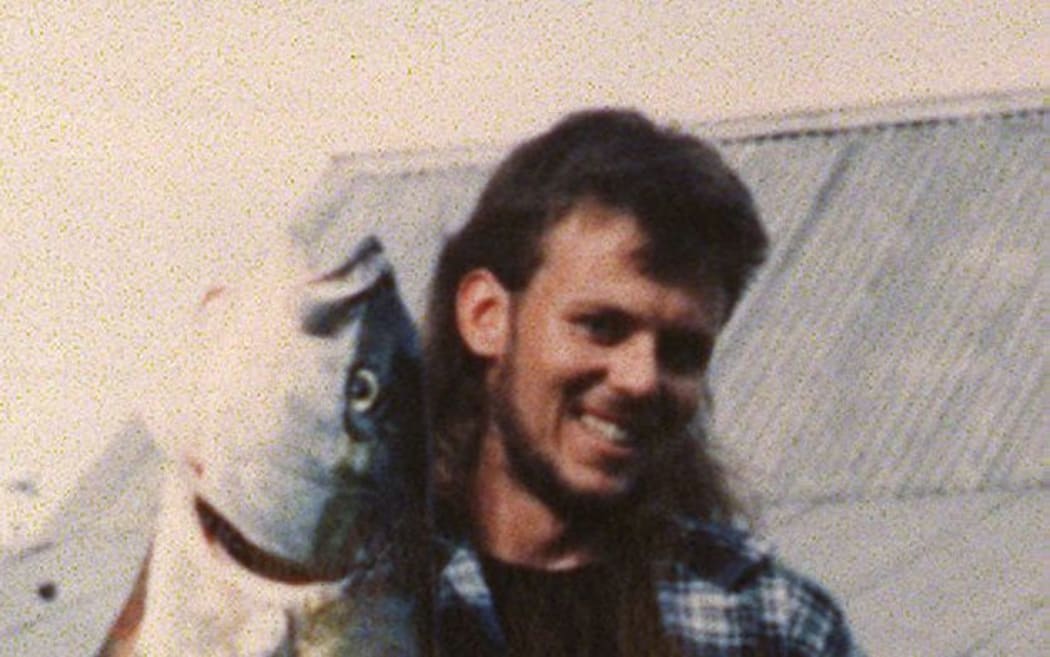

Dean Fuller-Sandys. Photo: Supplied

"A case like Gail's sounds very much like there are red flags that are evident in the testimony of people and so I think it's with good reason that people look at cases like that with scrutiny."

McKinnel was part of a team who was instrumental in the campaign for Teina Pora's murder conviction being overturned.

"We know from Teina Pora's case, for example, that a case can go untouched for a decade or more whilst a person sits in prison innocent. I don't think the time that has passed should be a barrier to these types of cases being looked at if there are good grounds to do that," he said.

Since the NZPIP was set up two years ago, it has received more than 100 applications from people who say they were wrongly convicted.

However, as the investigators, forensic scientists and barristers are volunteers, it's hard to make headway on some of the applications. They are also reliant on "blunt instruments" like the Privacy Act and Official Information Act to gather evidence.

McKinnel says the group is hopeful that the CCRC will provide people who say they've suffered a miscarriage of justice with an independent, formal route to get the case back in front of the courts. It will also be properly funded and will have the power to collect evidence, which the NZPIP does not have.

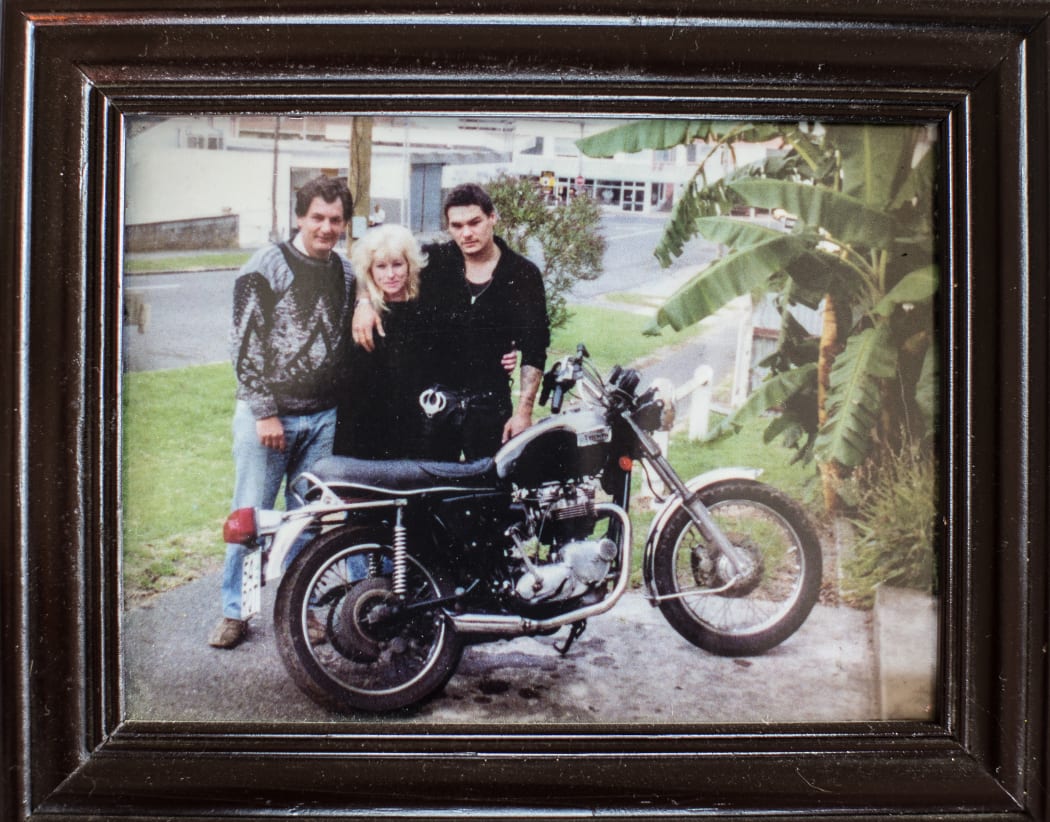

Stephen Stone (right), with his parents. Photo: Jason Dorday / Stuff

"I think that's a far better solution than a charity or non-governmental organisation trying to slowly grind their way through applications."

The CCRC will be an independent public body set up to review suspected miscarriages of justice, and to refer deserving cases back to the Court of Appeal. It is not a new function in the criminal justice system, but represents a change in who performs the function and how. Its statutory role requires it to make a considered legal judgement about whether an application has sufficient merit that an appeal court should consider the person's conviction or sentence.

Justice Minister Andrew Little said the Royal prerogative of mercy route provides the same function as the CCRC will. But the difference is that it will be an organisation with dedicated staff investigating the claims to determine whether an application should be referred back to the Court of Appeal.

At the moment, applications are dealt with justice ministry offices "if and when they've got time," Mr Little said. But the CCRC will be staffed by a board who is independent of the ministry and court system.

"I'm confident with the fact that with a dedicated staff with a good investigative powers, that people will be able to have faith their claim of miscarriage of justice will get the attention it deserves," he said.

Currently, the ministry receives up to a dozen applications for a Royal prerogative of mercy each year. But the grant of a pardon is extremely rare, and the last person to be pardoned on the basis of a wrongful conviction was Arthur Allan Thomas in 1979.

The Royal prerogative of mercy has the power to refer a person's conviction or sentence back to the Court of Appeal for reconsideration - and this is the real significance for those convicted who have used their appeals and remain dissatisfied with the outcome.

That power has been exercised on 15 occasions since 1995, which represents about 9 per cent of the 166 applications for the prerogative of mercy in that time.

A referral back to the Court of Appeal usually hangs on whether there is fresh evidence. But Little said the definition of new evidence was flexible. For example, this could include new information that wasn’t available at the trial, evidence that was hard to access, or a reluctant witness coming forward.

Little said he expects to get an influx of applications once the CCRC is firmly in place. A bill is currently being drafted to be heard in Parliament, and it’s expected to pass within four to six months. However, public submissions on how it is set up will be called for.

He was also confident that the CCRC will give people who believe they have suffered a miscarriage of justice the chance to have their cases reviewed by a body that is completely independent. And while Little believes volunteer organisations, like NZPIP, are helpful, the volunteers working on cases are often constrained by time.

“I think it’s very good to have those sorts of organisations, but I think in the end when it comes to justice it should not rely on whether or not you’ve got a volunteer who is prepared to put in the time and effort. Where in your case, the person down the road, doesn’t have that and therefore cannot get the same attention,” he said.

“The reason I want us to have a CCRC is so regardless of where you are and your circumstances, if you consider you are a victim of a miscarriage of justice there is a systematic way of dealing with that issue.”

Maney's applications to the justice groups, and her eventual application to the CCRC when it is formally set up, is not her first attempt to have her case reviewed under the grounds of miscarriage of justice.

She had started work on making a petition for an application for the Royal prerogative of mercy while she was in prison in about 2005 on the grounds that witnesses at both the trial, and retrial, had perjured themselves. She stalled on the application process because she wasn’t able to get the legal help she needed to complete the application.

“It’s a long process and a lot of legalities to understand, when you’re in prison it’s hard to have a voice out there and to get people to help you. You just don’t know where to begin,” she said.

Maney's case is currently in line to be reviewed by The Innocence Project, but she hopes that the new Criminal Cases Review Commission will be a means to get her case assessed faster.

Read more about the case, watch extended video interviews and keep track of the case with a summary of the characters, a timeline and map.

To find out more, you can subscribe to the full eight-part Gone Fishing series at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher or any other podcast app. Or, you can go to the RNZ homepage and click on Podcasts.