So I’m on my laptop, scrolling through Facebook, completely relaxed, when an errant post links memory and thought together into a toxic, self-doubting whole. I clench every muscle, swear aloud six times, click both of my index fingers – and then continue to scroll, my mind completely clear. My poor flatmates.

Leave me alone for any stretch of time and I’ll start talking to myself.

It’s not Shakespeare. While my interior train of thought has nuance and multiple syllables, this outward speech is juvenile, often just a repeated profanity or sentence fragment. It’s always in second person, always when I am alone, and always completely outside my control – like a frustrated older brother lives inside my head but leaves me alone when friends are over.

Henry Cooke Photo: Diego Opatowski / The Wireless

Luckily, he’s not the only one talking. My other streams of self-talk are much more positive. Just take a look at the alarms on my phone (“if you get up now you can make breakfast buddy!”), my to-do list on Evernote (“Wireless feature due september first!”), or listen to me scream Les Mis songs at my toaster. Of course I talk to myself. Everyone does.

“Egocentric communication” makes up for all the things the brain can’t do internally. Important dates. Complex problems. In my case: self-criticism. Deaf people even talk to themselves in sign language. It’s universal – some things need to be externalised or made material to feel real.

But it can feel pretty wrong, especially when it’s literally aloud. Crazy, narcissistic, childlike – something that you do when you’re too young to internalise, like moving your lips as you’re learning to read. The stoic adult turns over everything silently in their mind, penning brief, utilitarian reminders to themselves but otherwise saving the richness of human communication for other humans.

Historically, psychology has largely agreed with this view. Verbal “private speech” has long been considered a period of a child’s development, something that should drop away with your baby teeth. Lev Vygotsky and Jean Piaget separately established [pdf] modern thinking on the topic, and both studied it as a sign of cognitive immaturity in children, not something a fully-developed adult would or should engage in.

Vygotsky’s view of private speech as verbalised thought has generally held – children use it to sound out complex problems, to develop imaginary worlds, and to self-regulate. The speech is often fragmented or abbreviated, particularly when it’s “predicated” – concerning no new information or actual creativity – as both the speaker and listener already understand exactly what each is talking about.

READ Henry Cooke on his best friend’s dyslexia, which shut him out of the written world.

The fragments, the self-regulation – it all sounds awfully familiar, but I’m 22, get okay grades and am reasonably stable. There’s a decent body of research arguing that private speech doesn’t quite disappear in perfectly healthy adults – it just becomes a little harder to spot.

All but one of the 47 adolescents in this study engaged in private speech while completing a test, particularly after an actor in the room started doing it too. When given a variety of computer problems and an origami paper folding task to complete, every one of the 53 university-aged students in this study used some degree of private speech, particularly the fragmented, self-regulated variety.

Clearly, a lot of us talk to ourselves, but mostly when we’re alone and under some sort of stress. Both my mother and (real) elder brother admitted to frequently admonishing themselves in private – a cliché “Wait, you do that too?” moment if there ever was one.

Private speech has a huge social stigma – we associate it with narcissism at best, if not mental illness (“you don’t have any friends, nobody likes you”).

Social media serves the absolute opposite function of private writing, broadcasting your thoughts and feelings to an audience, but mimics its nuances

But shut your mouth and pick up a pen and nobody gives it a second thought. Writing for yourself is about as socially acceptable as wearing a monogrammed shirt: a bit self-involved, and who even has the time? – but well within normal behaviour. Diaries can be a window into madness when convenient, or just a handy way to chronicle one’s experiences for later reflection. The difference in perception has to do with intent: private speech is often compulsive, happening without any kind of planning or intelligent design, while writing something down requires some degree of effort and organisation.

Or does it? Maybe when one had to dip one’s quill in ink, and there was no easy audience on tap. In 2014 most of us type more than we speak, and for a much wider audience. Social media serves the absolute opposite function of private writing, broadcasting your thoughts and feelings to an audience, but mimics its nuances (“What’s on your mind?” Facebook probes). LiveJournal may have been the prototype, but I’ve never seen private writing-writ-large like it is on Tumblr. This may feel like the fifth pillar in a “narcissistic Millennials” thinkpiece – but is it possible we’re using these public platforms to talk to ourselves more than anyone else?

READ Elle Hunt on ‘Look Up’, “the spoken word film for an online generation” – and living life online.

As tempting as it was to not talk to anyone else for a feature on talking to yourself, I tracked down Michelle*, a Tumblr user who posts around 20 times a day, mixing an almost stream-of-consciousness account of her thoughts and feelings in with Tumblr’s standard gifs and male models. (Somewhat ironically, she asked to be included under a pseudonym.)

While it feels intimate, both to her and to readers, Michelle is not shouting into an abyss. “As I got more open on there, more people started to follow me,” she says. She generally doesn’t think about her audience while writing a post, or even while posting it, but often reads over things after posting them and changes her mind. Thank god for the edit button, right?

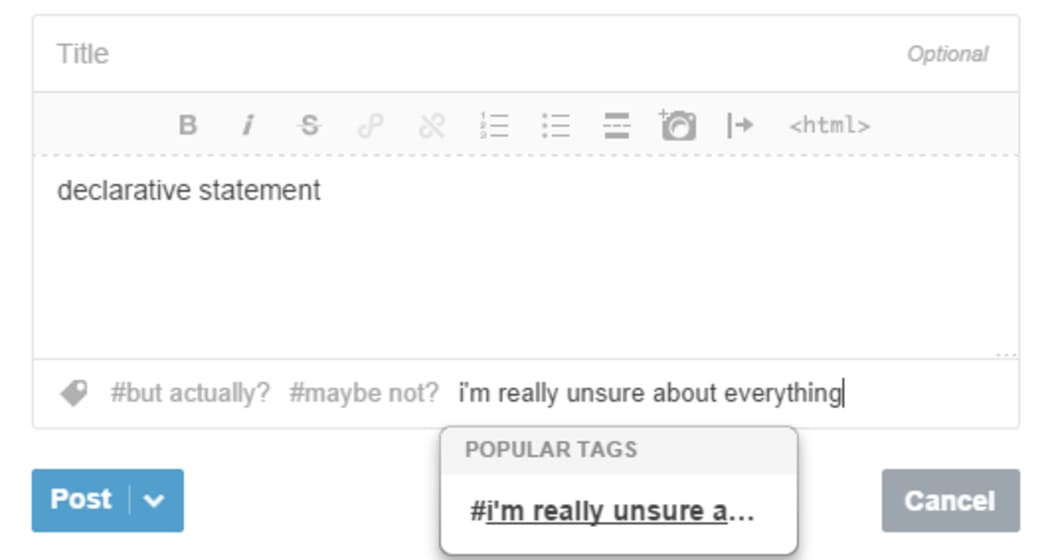

Tumblr is great for talking to yourself in public. Part of this is just the ease of posting half-formed thoughts (proper sentence structure is not only optional on Tumblr; it’s almost discouraged), but part of it stems from careful misuse of the ‘tag’ form. Text written in the tag form will display in a less ostentatious grey text below the main body of a Tumblr text post, and needs to be scrolled through to be read properly.

How Tumblr tags work Photo: Unknown

“The tags are where the honesty is,” explains Michelle, who often questions whatever she just wrote and her reasons for writing it in the tags below a text post: “It’s kind of like an action and reaction”. This constant questioning of things one just thought simulates the loops we put out brains through perfectly, allowing one to state something and its opposite simultaneously.

Not all of Michelle’s private thoughts actually make it into a Tumblr post – it’s not quite that instinctual. She does compulsively type things out that she knows she will never post, “so I can process it and have that for myself, then just trash it”.

This resonates with those of us who’ve drafted emails we’ve had no intention of sending, who were angry when it turned out Facebook was tracking status updates we wrote out but never posted – and even though Google searches are admissible in court, we’ve all searched for some things we’re not proud of. Is there any real difference between me typing “f**k f**k f**k f**k f**k” out and actually saying it aloud?

Henry Cooke Photo: Diego Opatowski / The Wireless

No, but that’s missing the point. Talking to yourself is useful, not just for revving yourself up or verbalising a difficult problem, but for actually knowing yourself. The part of me that wants me to remember everything bad I have ever done is probably making me a more conscientious person, even if I think he’s a bit of a dick. The part of you which idly types out the name of someone you know whenever you are on Facebook might know more about your heart than your regular brain does. You contain multitudes, multitudes which will inevitably disagree with each other. Your personality is not a continuous whole. The tags are as important as the post.

This content is brought to you with funding assistance from New Zealand On Air.