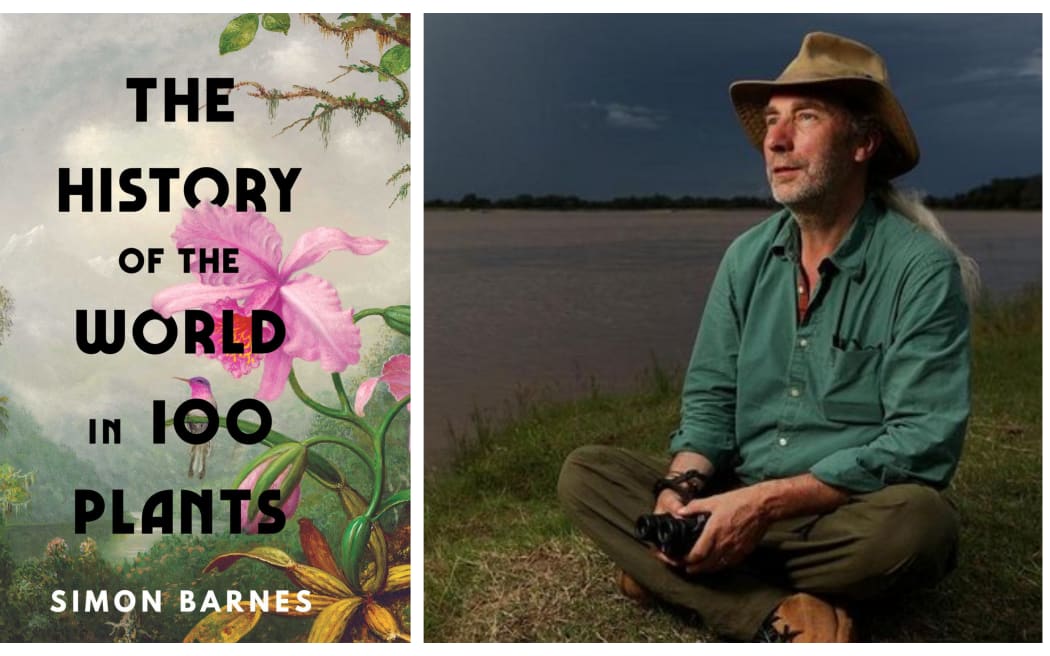

British writer Simon Barnes delves into the deep, ancient relationship between humans and plants in The History of the World in 100 Plants

“There's rich history in practically every plant that grows,” he tells Kathryn Ryan.

Photo: supplied

Thousands of years ago, the strangler fig helped foster early humans, Barnes says.

“If you were a hunter-gatherer on the savannahs of Africa, you're going to do your work when the sun comes up until it gets too hot to work, round about half past nine.

“And then you're going to sit in the shade and wait until it gets cooler again, you've got these hours in which you can rest up.”

Strangler figs were the trees that provided the deepest and coolest shade.

“The early proto-human hunter-gatherers sat there, and they had this downtime in the shade. They could communicate, they could sing, they could invent religion, they could talk to each other, and they could build a society.

“I believe that human society began in the shade of a strangler fig.”

Clothing made from plants such as flax and cotton was a signifier of status within early human societies, Barnes says.

“Why did humans in warm climates first start wearing clothes? I bet it was all about prestige and a lot of things when you look back, came about from the dominance hierarchy and how you showed you're more important than somebody else.”

Across history, we've used plants for medicinal, recreational and also darker reasons, he says.

“There are plenty of poisonous plants. And it's not because they were put there by an evil genius or anything like that, [their poison is] a naturally evolved defence against being eaten.

“Everything depends on plants to eat - that doesn't mean plants have to take it lying down.

“They don't have mobility, they can't run away. So many of them have different kinds of poisons to make them unpalatable, even to the point of being to some species deadly.”

Humans have long used plants to alter consciousness, Barnes says.

“It really is a basic human instinct to get high, to use plants in various forms to change one's state of consciousness.

“Here where I live in the springtime, the place is full of barley. We grow barley in order to brew beer and to make whiskey. It's not a daily staple, it's just for many people that daily essential.”

A humble fungus named Penicillium notatum changed the world forever when Alexander Fleming discovered its powerful anti-bacterial properties in 1928.

“[Penicillin] changed the possibilities of life on the planet, reduced infant mortality and gave people much more opportunities to live to grow and be old.

“And now there are 8 billion of us, thanks to a fungus.”

Throughout history, trees have reshaped the world, too, Barnes says,

The cinchona tree, found in South America, helped usher in the colonial era as a game-changing treatment for malaria.

“The Spanish, who had most of the areas of South America where the cinchona tree grew were very anxious to keep hold of it.

"But eventually it was smuggled out by a gentleman called Charles Ledger, and he offered it to the British and they weren't that interested.”

The Dutch were, however, and the British soon realised their mistake.

“[The Dutch] established plantations of cinchona trees in Sri Lanka and in southern India.”

The prophylactic properties of quinine derived from the cinchona tree paved the way for full-scale colonisation, he says.

“[Then] you can have real colonialism, not just military outposts and trading posts. You can start bringing families and breeding children and so forth.”

Simon Barnes is the author of many books including the bestselling Bad Birdwatcher trilogy, Rewild Yourself, On The Marsh and The History of the World in 100 Animals.