Take some old weather records. Add citizen scientists. Mix in machine learning from Microsoft's ‘AI for Earth’ project.

And what you end up with is something that might help predict future weather patterns.

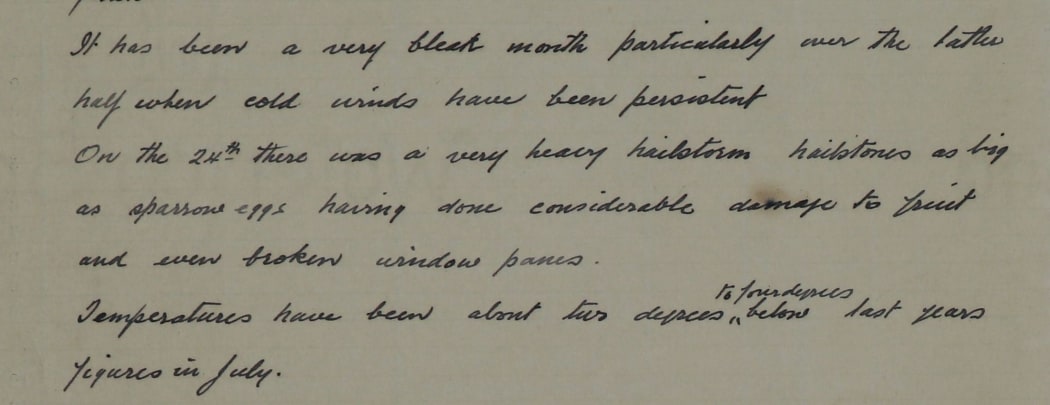

Weather records from Kerikeri, June 1939 - "hailstones as big as sparrows' eggs." Photo: NIWA

Find Our Changing World on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, iHeartRADIO, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic or wherever you listen to your podcasts

By all accounts, the winter of 1939 was a long, cold, snowy one. In the last week of July, there were reports of snow in many places, from Bluff to the lighthouse at Cape Reinga.

It’s been dubbed ‘the week it snowed everywhere,’ and NIWA researchers have scoured old weather records to find out exactly where it snowed, and how much snow fell.

They hope these records from the past will help predict snowy weather in the future more precisely.

Photo: RNZ

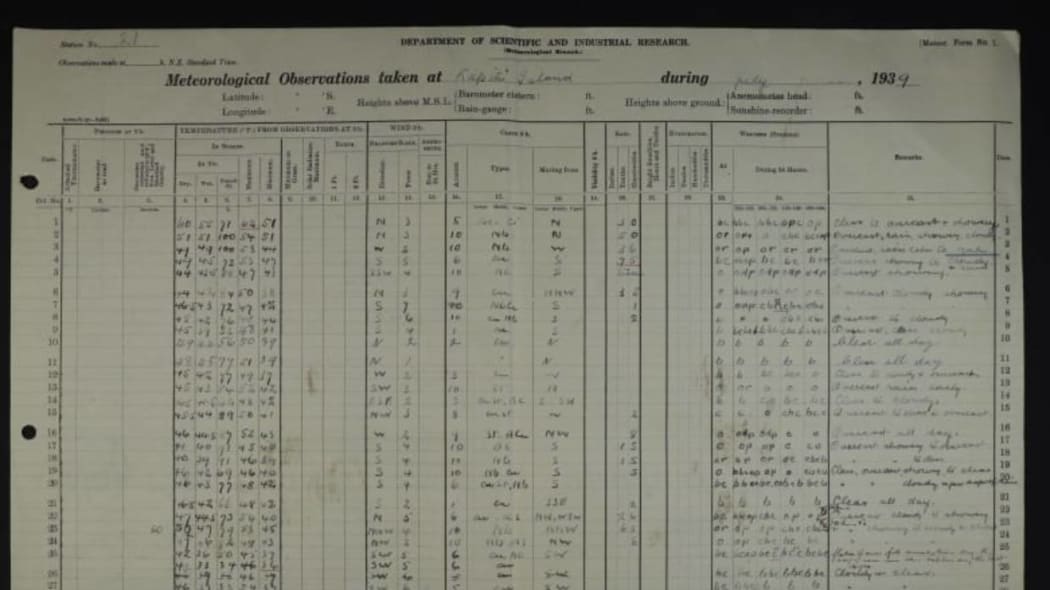

Andrew Lorrey says NIWA has countless boxes of old weather records, collected from around New Zealand and the Pacific. Local observers filled out precise hand-written daily reports of sunshine hours, rainfall, wind speed and direction – and, sometimes, snowfall.

“They were quite dutiful in doing the rain and the obs every day, no matter what was going on,” says Andrew.

He says NIWA still has the first official weather records for New Zealand, that go back to the 1850s. “Basically, the barracks at Albert Park [in Auckland], the Royal Engineers, 1852 … those were the first truly official Government regimented observations.”

Andrew has also helped find New Zealand’s earliest, unofficial weather records, from Reverend Richard Davis. The Reverend’s weather diary was found in the Special Collections of the Auckland Public Library. It goes back to 1839 with daily weather observations from the Far North, including records of snow persisting on the ground for several days.

“We’re wanting to understand those types of extremes, and how and why they happen for New Zealand. And whether they are something we’re going to see less of, or is it something we’re going to see more of with climate change,” says Andrew.

Andrew says it seems that Northland experiences snow every 60-80 years.

The Davis diary, which has UNESCO Memory of the World status, has been copied and digitised, and Andrew has made a start on getting the official weather records digitised as well.

Weather records from Kapiti Island, July 1939. Photo: NIWA

He began with records from the 1939 week of snow, using citizen scientists to decipher the hand-writing and enter the data. He says eight observations of the same number gives a very reliable data set.

“People are incredibly helpful. They’ll come along and key in bits and pieces as they’ve got five minutes to spend. And that’s five minutes we didn’t have to spend.”

These weather records have been used for Microsoft’s ‘AI for Planet Earth’ project, designed to improve machine learning as a tool for digitising tabulated numeric scientific data.

“It’s a very difficult thing to get right. No one has really solved it yet.”

The weather records provided an accurate data set that could be used to train the AI.

“Being able to use these data for the betterment of humankind – that’s the goal,” says Andrew.