Those occupying the whenua at Ihumātao say they will stay until it is safe from development but how did things get to this point? Archaeologist David Veart says it was the failure of heritage protection legislation.

Photo: RNZ / Dan Cook

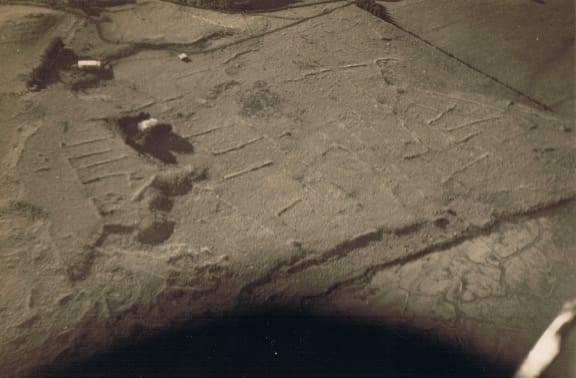

In 2014, after the Super City was formed, the government and Auckland Council designated the 32 hectares of Ihumātao as a Special Housing Area (SHA).

Sitting right next to the site, the Ōtuataua Stonefields reserve is protected as one of New Zealand’s key birthplaces.

In 2016, Fletcher Residential – a wholly-owned subsidiary of Fletcher Building – bought the land in order to build 480 houses.

Te Kawerau ā Maki - the iwi considered mana whenua at Ihumātao - remains divided on the land dispute.

Its mandated iwi group - known as Te Kawerau Iwi Tribal Authority - supports the development, having made a deal with Fletcher Building to have eight hectares of land returned to their people.

But others within the iwi want the land protected.

A group made up of mana whenua and local community representative SOUL (Save Our Unique Landscape) say the land has historical, cultural and archaeological significance and should be left an open space or returned to mana whenua.

According to SOUL, the land was taken 'by proclamation' during the Waikato invasion in 1863.

It was confiscated under the New Zealand Settlements Act, thus breaching the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi agreement.

In 1867, the land was acquired by Crown grant.

It was on-sold to Pākehā settlers and was a privately-owned farm for the last 150 years, before being bought by Fletchers.

Ihumātao land battle: a timeline

Dave Veart belongs to the Auckland Heritage Committee of the Institute of Professional Engineers and has been appointed as a member of the Auckland Council's Heritage Advisory Panel.

He was asked by SOUL if he would be their archaeologist.

Dave Veart at Otuataua Stonefields Historic Reserve Photo: RNZ/ Tim Watkin

“I am completely unsurprised at what’s happening at the moment, these people (SOUL) have built – very quietly and without anyone taking much notice – this incredibly strong cause which has obviously pushed a lot of buttons in a lot of people around the country.”

Veart says the failure of the heritage protection legislation has caused the current situation.

The courts are interpreting the Act to mean the land at Ihumātao has to be regarded purely on its own merits, he says.

In 2016, when Fletcher bought the land, Heritage New Zealand granted archaeological authority for the project.

“This is where I’m saying the legislation is failing us. You’ve got the bizarre situation of standing up in the Environment Court with Heritage New Zealand defending the rights of a developer to destroy a site which they recognise as being important. They’ve stood up in previous courts and argued for the protection of this land…”

He says Heritage New Zealand can no longer make the argument they’ve used previously because in a court decision regarding a petroleum exploration company in Taranaki, the court said the objection from iwi and Heritage authorities was invalid because it dealt with the relationship of the land in relation to the land next to it.

“Its importance was driven by where it was, not so much what exactly it was. That’s the problem here, it’s been cut off to its landscape, you’re just looking at paddocks as if they existed in some sort of vacuum.”

It’s complicated, he says.

“The creation of the Super City destroyed any corporate memory of the city. The situation that’s led to the declaration of this land as a special housing area is…unbelievable. That a piece of land that had been seen as having high heritage importance was signed off for an SHA, those ones were meant to be ready to go, houses ready to go and tick, tick, tick…obviously someone didn’t know what was going on and if they did they weren’t saying.”

He says it’s the reason he got involved in the cause.

People continue to occupy Ihumatao after protestors were served an eviction notice which led to a stand-off with police. Photo: RNZ / Dan Cook

Veart was the archaeological witness for the SOUL group in the Environment Court.

“Archaeologically, when you’re assessing the value archaeologically…you’ve got to fit it into a larger landscape. Now what’s happened, case law in the last few years has said that each piece of land has to be taken purely on that piece of land within its European boundaries.”

He says the land at Ihumātao, almost anywhere else, would be interesting but that’s about it.

“What gives it it’s huge importance is the fact that it’s next to one of the most complex archaeological landscapes in the country, Stonefields reserve.”

The first gardeners to arrive in Aotearoa set up gardens on the land, he says. Ōtuataua Stonefields Historic Reserve is the area where these gardeners learned to convert their skills to providing food for the growing city of Auckland in the 1840s and 50s.

“This is the whole story of human settlement and land use since the beginning of human arrival and this is the last piece of land we can tell that story in that way. The fact that you have to try and stand up in a court and argue that this piece of land has to be taken just purely on its own merits is ridiculous and needs some legislative change to sort that out in my opinion.”

The tino rangatiratanga flag is seen at Ihumātao as the day draws to an end for protesters on the land on Friday, 26 July. Photo: RNZ

Dave Veart wrote one of the original reports in 1983 that lead to the purchase of the Ōtuataua Stonefields reserve when he worked as a Department of Conservation historian.

“The reserve was created because the land owners wanted to quarry the land, the thing about the Stonefields is that they’re built on stone and stone has a value, the land next door was considered, it’s part of the same landscape but at that stage in the early 1990s it wasn’t under threat.”

Fletcher refers to part of the land as an 80 metres buffer zone, which contains burial caves, but Veart says this is land they would have never actually got permission to build on.

“What’s being sold as a buffer zone in fact are pieces of land that couldn’t be developed anyway without a huge amount of legal intervention.”

It’s also important to look at the peninsula Ihumātao sits on, says Veart.

“Up until the late 1960s, we just had this amazing landscape with giant pā sites and gardens and all sorts of things, now we’re down to the last few remnants, the Stonefields reserve is really the only part that has any decent protection.

“We get upset about the destruction of other people’s heritage… but what we’ve managed to do in this landscape is destroy a remarkable amount of our own heritage. This is the last bit left, it seems absurd that we’re trading it off like this.”