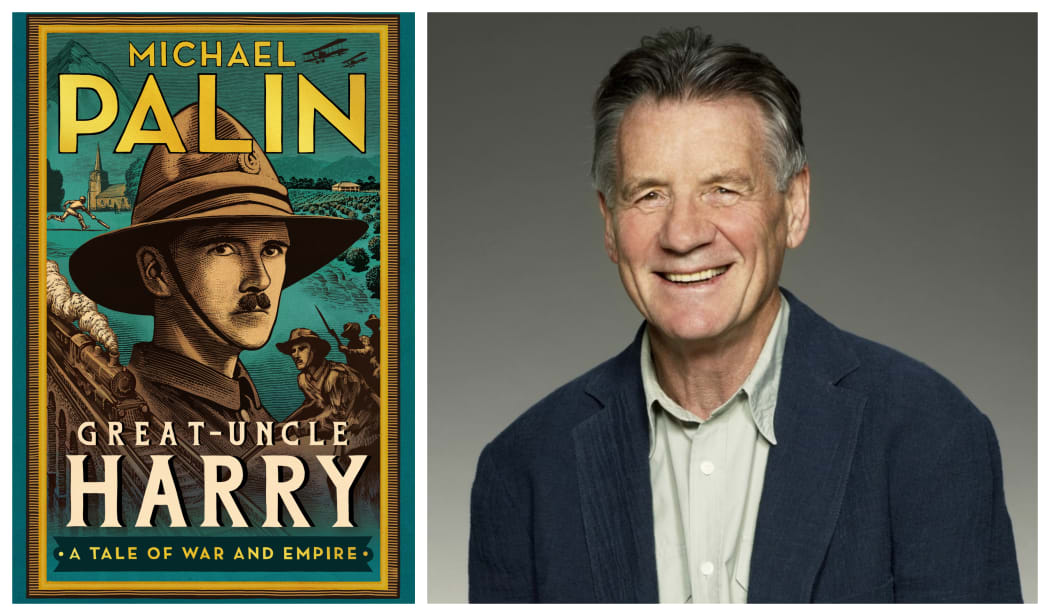

Michael Palins book 'Great-Uncle Harry: A Tale of War and Empire' Photo: Michael Palin

Comedian, broadcaster, actor and author Michael Palin's latest book follows the extraordinary life and tragic death of a WWI soldier fighting with the New Zealand Division: Great-Uncle Harry: A Tale of War and Empire.

The biography tells the story of Sir Michael's uncle Harry (Henry William Bourne Palin), including his time spent in New Zealand, up until his tragic death, killed by a sniper in 1916 in northern France during the Somme.

Speaking from Edinburgh on his book tour, 80-year old Sir Michael told Jim Mora the book's release has come after a period of sadness and change in his life.

"Early this year I lost my wife, and well, I know about sadness now."

His wife Helen Gibbins died in May, after 57 years of marriage. She was diagnosed with kidney failure, and decided to end dialysis.

"That was keeping her going, but for a life that she didn't want," Sir Michael said.

"She was a very independent woman. She didn't want to just carry on with people just helping her across the room every time and cooking every meal and helping her across the road ... so in the end she decided, and we all agreed, that she would stop the dialysis, and that was her decision, taken by us as well.

"I think having made that very brave decision, in the last 10 days she was happy. Because they were able to give her more than the usual amount of drugs, so she was without pain, she was being looked after in the wonderful hospice, the family were all around, and she wouldn't to have to face a life of total dependence on others any more, and pain as well, so I think in a way she knew - it was a relief, and it helped us to bear it too."

Sir Michael too has had his own health battle, and has had a heart valve replaced and one repaired, but says the surgery has helped and he recovered well.

"You get older, and you're aware that things get a bit creakier, the machinery gets a little bit rusty, but so far so good, and I'm okay."

The book is the result of hundreds of hours of detective work from Sir Michael, desperate to uncover the details of an ordinary man who lived an extraordinary life.

Harry had been a footloose soul before the war, which led him to New Zealand. He had a public school education, his dad was an Oxford don, but he was restless.

"He couldn't find the right place, he wasn't connected with the conventional career paths", he didn't make much money or have much time for authority, Sir Michael says.

"But the decision to go to New Zealand in 1912 I feel that was one of the best decisions, because it was his own decision ... it didn't cost the family much, he wasn't having to join a company or take on a corporate job or anything like that.

"A lot of this is hypothetical, I don't have exact proof of everything that was going through his mind at the time. Although I do have his war diaries, almost every day he made an entry in his diary, so you get some idea of how he looked at the world."

Harry emigrated to New Zealand, he went off to become a farm-hand, and ended up working in Canvastown, at the top of the South Island near Picton.

"And I think those were happy years for him there," Sir Michael said. "I think he felt he was with mates - he was obviously a man who liked the company of friends, and I think he was well looked after ...and I think those two or three years he spent in New Zealand before the war were the happiest times, happy because he'd made the decision to do what he wanted to do rather than what his parents or his family or the country thought he ought to do."

But then came the war. Harry joined up with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and was part of the 12th Nelson Regiment.

Sir Michael says Harry had been expecting to be sent to fight closer to England, in Western Europe, but he saw action first at Gallipoli.

"He spent four months in Gallipoli - escaped without a scratch, which is utterly remarkable really at that time. And was transferred to France, and fought at the Somme."

His diary entries reflect a matter of fact man with a casual bravery. He wrote about the landings at Anzac cove and going swimming there with shells falling nearby.

"All the people who took part in the war I suppose had to accept this was something they were swept up into, there were very few deserters, which always surprised me considering what they were going through," Sir Michael says.

"But I think what kept Harry going and his fellow New Zealanders, was they had a pride in fighting for the New Zealand army, which was one of the smaller armies, but considered quite highly by the top brass ... but also he felt he was doing it for his friends.

"It wasn't about strategy, it wasn't about politics, it wasn't about what sort of ammunition they were given, he wasn't someone who analysed anythig too much, he was just there with his friends trying to do the best for them.

"And I think that might be the attitude that gets you through... and he kept going, his diaries showed that he was continually moving behind enemy lines, bringing back bodies, bringing wounded down to the ships on the shore, carrying ammunition up to the artillery positions, he's always on the go. And I think that's because he feels he's with mates that he likes and respects.

"When he does describe assaults - and he does it very well - but he always writes down the names of the people who have been killed, and I think that's very indicative of his loyalty to friends..."

After serving in Gallipoli, Harry was able to have eight days leave in Kent, back in England.

"But about 100 miles away they were killing each other in the trenches.

"He went back to fight, took part in the last big assault by the New Zealand forces at the end of the Battle of Somme in 1916 and that's where he was killed."

Sir Michael visited the field in France that Harry was trying to cross when he was shot and killed by a sniper during the Somme.

"I know the patch of land ... but you can't see much now. He never got to the top of the ridge. I felt that quite deeply."

Why does he think there is still so much shock and sensitivity to the horrors of of WWI?

"Because so much of the fighting was hand to hand", compared to the machine-led WWII", Sir Michael says. "These were just men sent out deliberately, to be ammunition."