A tale of two sisters

During her lecture, June Northcroft Grant talks about two of the most famous guides at Whakarewarewa

My story is woven around the lives and times of colonial settlement in Aotearoa in the 1800s, in this village set amid the steaming volcanic landscape of the Waiariki, from the shores of Maketu to the majestic mountains, Tongariro, Ruapehu, and Ngaruhoe, mai I Maketu ki Tongariro.

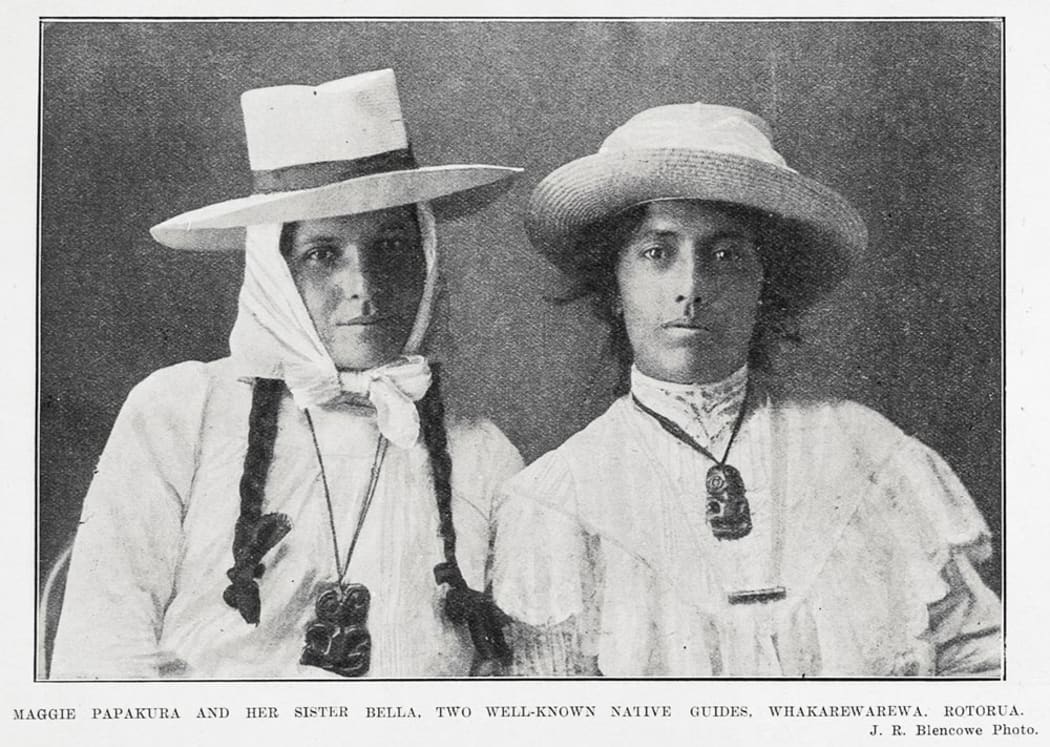

Two of the most famous guides at Whakarewarewa in this era were sisters.

Photo: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection

Bella Thom was the elder, born to Rakera Ihaia and William Arthur Thom in 1870. Bella did not move far from the village during her lifetime apart from attending school and touring with her sister Makereti to the South Island and Australia.

Bella’s father had ensured that the Thom children were well educated and sent them to schools in Tauranga and later to Hukarere Girls' School in Napier to complete their formal education. Their first language was Māori as they had been raised in the village with their Wahiao whanau around them.

A bicultural education meant that Bella was able to move easily between Pakeha and Māori worlds, becoming a popular and memorable guide in her time.

She learned the skills of hosting and guiding visitors from the legendary Guide Sophia Herangi, a survivor of the Tarawera Eruption who sheltered 62 people in her whare Hinemihi on the night of the eruption in 1886.

In 1905 Bella was the first guide to be licensed, receiving Guide Certificate No.1 when she was 35 years old, although she had been guiding since the late 1800s.

Bella married twice as beautiful maidens are wont to do, and each time to carvers. Tamati Paora carved this whare whakairo, Wahiao (where the lecture is being held), and her second husband Aperahama Wiari carved Bella’s whare at the top of the hill here in Whakarewarewa. Bella had no children but whangaied Whakarato Haira and many children living in the pa in the 1920s including my father. If you turned up at dinner time, you got fed, if you turned up at night time you slept in the whare.

In 1939 Bella suffered a stroke and spent the next eleven years in Rotorua Hospital. Although she never returned to guiding at Whakarewarewa, her guiding number was never re-issued, and she was always acknowledged as the head guide during that time.

The inimitable Guide Bubbles (Dorothy Mihinui) always spoke of Bella’s influence and credited her with instilling the intrinsic values of manaakitanga, shown in the way she referred to manuhiri as visitors rather than tourists.

Bella passed away in 1950 at the age of 80, and is buried in our family urupa next to her home, at the top of the hill alongside her husband Aperahama Wiari.

Maggie Papakura Photo: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection

Bella’s sister Margaret Pattison Thom, later widely known as Makereti (or Maggie) Papakura, was born at Matata in 1873.

She had been taken from her mother soon after she was born to live in the rural community of Parekarangi where she was raised by her mother's paternal aunt and uncle, Marara Marotaua and Maihi Te Kakau Paraoa.

On leaving school, Makereti came home to live at Whakarewarewa, the ancestral home of her people where she made an enormous contribution to her whanau and hapu. She passed on to them what she had been taught about the customs and tikanga of Ngati Wahiao, teaching karakia, waiata and moteatea.

She was also very politically aware and had many friends in Parliament, helping Sir Apirana Ngata with his election campaigning in the Rotorua district. Te Rangihiroa Sir Peter and Lady Buck were frequent visitors who came to live in the village at various intervals, along with Sir Maui and Lady Pomare.

Makereti was able to offer an intelligent perspective on native affairs, to which she also contributed through the pages of ‘letters to the editor’ often in angry retribution for racist commentary which she refused to let lie.

The Papakura surname was acquired almost by chance, as her friend and Oxford University colleague T.K. Penniman wrote in the introduction to her book The Old Time Māori:

She came by the name in a curious fashion. Europeans who saw her as a child naturally shortened her name to Maggie, and an unusually inquisitive visitor tried to find out whether she had another Māori name. She had not of course but was willing to oblige them, and as she happened to be standing near a well-known geyser called Papakura, she promptly said ‘Papakura’ and the name stuck.

The guides were (and are still) significant in passing on important tribal knowledge of our environment, our customs and way of life to visitors. Makereti sought to correct the impression any of them may have brought with them that Māori were savages and uneducated. Her demeanour, elegance, intelligence, beauty and knowledge impressed many.

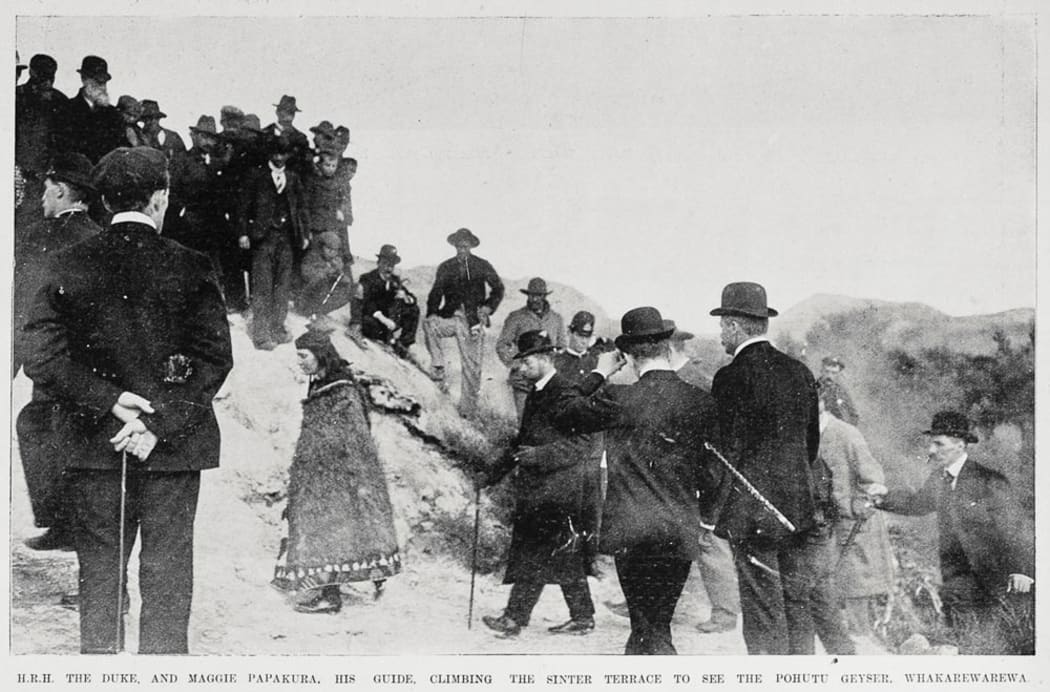

One in particular was Richard Staples-Brown, who kept up a correspondence with her when he returned to his native Oxfordshire early in the 20th century. They met again when Makereti took her kapa haka group to the Crystal Palace in 1911 for King George’s coronation, having been a guide for the King when he had visited Whakarewarewa ten years before as Duke of Cornwall and York.

The future King George V and Maggie Papakura in Whakarewarewa, June, 1901. Photo: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection

The relationship with Richard was rekindled leading to a romance that enticed Makereti to leave her homeland and beloved whanau for marriage in England in 1912. Based in Oddington in Oxfordshire, the Staples-Brown family were not the aristocratic, titled family of media conjecture, but still well-off landed gentry.

In 1926 she enrolled as a student at the University of Oxford to study for a BSc in Anthropology. A lifetime collection of notes, journals and diaries was collated and rewritten for her thesis. The same year she journeyed back to New Zealand to consult her elders on the content of her work and gain their approval. The Old Time Māori was published in 1938, eight years after her death.

Her request to be buried in Oddington cemetery was honoured by her grieving family, her son Te Aonui and sister Bella. A memorial was raised in her memory at Whakarewarewa a year later and is in the family urupa just up the hill.

More information

Paul Diamond’s radio documentary about Maggie Papakura (Part One)

Paul Diamond’s radio documentary about Maggie Papakura (Part Two)

About the lecturer

June Northcroft Grant

June Northcroft Grant Photo: Waitangi Rua Rautau Lectures

Te Arawa, Ngati Tuwharetoa, Tuhourangi, Ngati Wahiao

Born in 1949, June was educated in Wairoa, Whanganui and Rotorua.

She is a direct descendant of Makereti (Maggie) Papakura, a well-known guide of Whakarewarewa Village in Rotorua, central Northern Island, where thousands of tourists were escorted through the scenic attractions of the area. Makereti has had a strong influence on June's life and work.

Her father was Major Henry William Northcroft, a leader of the 28th Māori Battalion.

June graduated from the Waiariki Polytechnic in Rotorua in 1989 with a Diploma of Craft Design. She is inspired by her ancestors and her work is often interwoven with powerful figures and stories from her own tribal history.

She has received numerous awards for her achievements in arts and culture and participated in many contemporary Māori art exhibitions not only in New Zealand but also in Canada and Australia.

She has won the prestigious MWDI small business award, and the Black Pearl Award for Māori women’s leadership. In 2010 she was declared an Officer of the NZ Order of Merit for her services to Māori art and breast cancer awareness.