I’m riding shotgun in my friend Leon’s car back from dinner in Matakana. It’s night, and there’s a dense fog covering the road so that we can’t see more than ten feet in front of us. When Leon had mentioned it on the way out, I’d declared “Cool. I love driving at night.” But now I’m nervous.

Photo: Illustrations: Devon Smith

As each set of headlights careens out at us from the dark I visibly tense and make little whimpering noises. “I thought you liked driving at night,” Leon reminds me. “I thought I did too,” I reply.

I can’t drive. I don’t even have my learner’s. I try not to judge people on their driving, as I have no idea what they should or shouldn’t be doing. But when you don’t know how to operate a car yourself, climbing into a passenger seat is a little like strapping yourself into one of those rides at a carnival that has only been assembled off that morning. You just have to have faith that the people running the show know what they’re doing.

There was a time I wouldn’t have equated driving with danger at all. But here in the car with Leon, facing the fog, I’m forced to question what exactly changed.

*

Going fly fishing has always been something of a tradition in my family – that is to say, my dad always loved fishing, and we made a tradition out of his failed attempts to get my sister and me to love it as well.

Dad and I had a great relationship, but fly fishing was one of the biggest areas of disconnect between us. I have in my possession a thick book on the subject that was gifted to me by dad while he was ill, and which I’ve yet to read. (I say “yet” – I’m never gonna read it.)

I loved the adventure of the fishing trips, though. We’d leave while it was still dark, so as to get a head start on the traffic; I’d be wrapped up in a duvet, having been unable to sleep for excitement. Then we’d get McDonald’s for breakfast. (Win!)

I always felt completely safe. My dad drove a big car and exuded calm. I trusted him implicitly. I was a devout Catholic, and Dad was God. With him at the helm, it was simply not an option that we would ever come to harm.

The first day fishing was tough, and I gave up early, retiring to the most comfortable rock I could find, frustrated and reminded of all the reasons I don’t like fly fishing.

My dad passed away last year. For five years he’d been slowly declining due to Motor Neuron Disease. In the early days of the illness, his voice went first and he would carry around a notebook so he could communicate. It was at this point, just as his legs were starting to weaken, that he suggested we take a fishing trip to Turangi.

We headed north in his Land Rover and I played him songs from compilation CDs I’d burnt for the trip. He liked The Mountain Goats. He liked Okkervil River. He didn’t like Beirut. As Dad couldn’t talk, I spoke for both of us, buying stuff from the store, picking up the key from the lodge we were staying at.

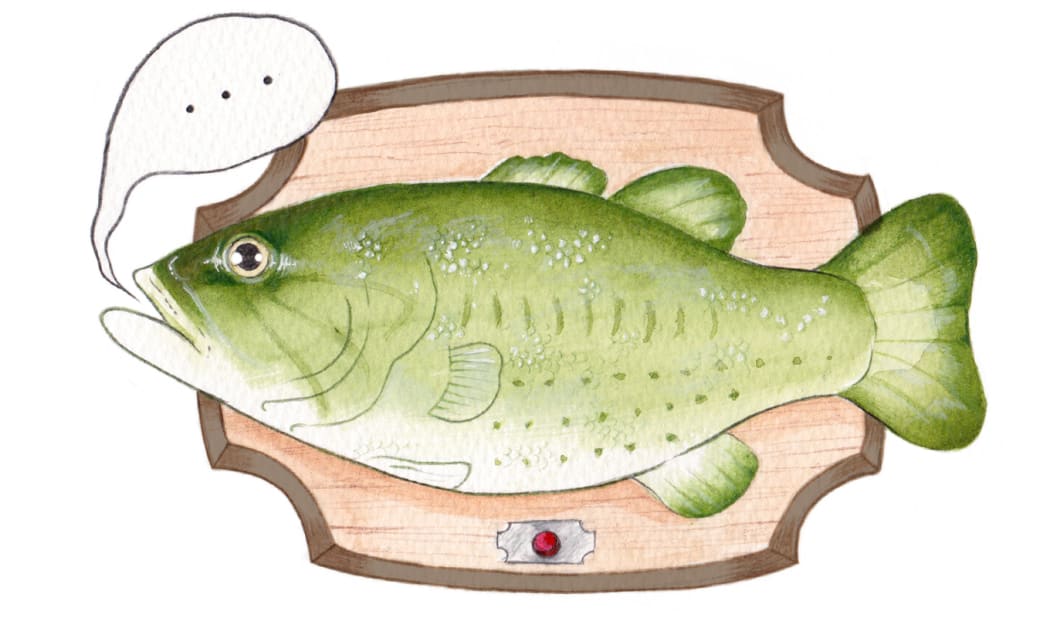

The lodge was small and cluttered and had an animatronic singing fish on the wall by the name of Big Mouth Billy Bass, who’d wag his tale whenever we passed and belt out kitschy covers of whatever songs his creators had managed to get the rights to. Billy put his own take on the lyrics – ‘Take Me To The River’ fit nicely already, but you could hear his creativity starting to strain with ‘I Will Survive’, and by the time ‘Act Naturally’ came around he was basically taking the piss.

Dad and I rolled around Turangi for two or three days looking for fishing spots. Here there was also fog. It hung on the lake, wrapped itself around the reeds and mingled with the steam from the thermal springs.

The first day fishing was tough, and I gave up early, retiring to the most comfortable rock I could find, frustrated and reminded of all the reasons I don’t like fly fishing – mainly that I’m not good at it, and if I’m not good at something I will immediately give up on it. This complete lack of willpower is the main reason I’m not good at most things.

That night, sitting around a fire, Dad had a coughing fit and retreated to the car. I joined him and he scrawled on his notepad for me to read: “I am forced into exile because of the smoke.” Later, when he wasn’t around, I ripped this page out to keep for myself. I felt immediately guilty about it, as if I’d stolen his voice from him, like Ursula in The Little Mermaid.

One night I sat wrapped up in the car on a beach, watching Dad cast off into Lake Taupo. There stood a man who earlier that week had tripped himself up on his own ever more clumsy feet while walking up Cuba St, standing waist-deep in the waves like it was nothing.

I turned the headlights off briefly to preserve the car battery. When I turned them back on Dad was nowhere to be seen. I jumped out of the car and ran down to the shore, looking around desperately. Suddenly the whole venture seemed like the dumbest idea in the world. What were we thinking? What was I thinking? All it would have taken was one sizeable wave to knock Dad off his feet. And there I was hiding in the car like a baby.

Then he appeared again, out of the dark, striding up the sand, rod over shoulder. He shrugged slightly as if to say “No luck” and I expressed my condolences, keeping forever mum about how scared I’d been.

Later, in the farthest stages of his regression, I would come to know my dad’s strength. His baffling ability to be open and generous in his attempts to come to terms with what it means to die. But in those early stages it was all so raw and confusing. During that trip I felt unsafe in the car with him for the first time in my life. He seemed nervous, unsteady. The communication divide between us meant I could no longer trust him to be honest about his abilities. I worried that he so wanted the trip to happen that he would push himself and put us both in danger.

Needless to say we didn’t crash.

Nor did we catch any fish.

*

I realise now, in the car with Leon, that since that trip I’ve been scared of cars, let alone the prospect of learning to drive one. I’m scared of the responsibility. I’m scared that… well no, I know that I won’t be good at it. It requires hand-eye coordination. It requires being OK with being bad at something for long enough that you become good at it. Or, if not good, non-lethal.

I know that if I’m to be half the man my dad was (and half the woman my mum still is – let’s not leave her out of this) that means being able to look down at the helpless little person I might one day find myself responsible for and know that they at least feel safe riding next to me. Even if that means having to be scared for the both of us.

But that prospect seems pretty far away from me now, cowering in the passenger seat as Leon propels us into the night and the fog swallows us up over and over again. I feel like a fish ripped from a river into the cold harsh suffocating air – but there’s no going back now. In my head I’m singing “Take me to the river, drop me in the water…”

I think back to the last day of the trip. After stopping off at a café for pies and Red Bulls, I returned to the car to find Dad had written another message for me.

“I’m feeling more and more, all the time, like a fish on the end of a line.”

The rhyme, I think, was unintentional. Then, with a smile in his eye, he followed it up:

“I’m not sure God has a catch-and-release policy.”

This content is brought to you with funding assistance from New Zealand On Air.