Eight years after it was announced, the proposal to create a vast ocean sanctuary around the Kermadec Islands has stalled again. The Detail traces the sanctuary's history and why it's never eventuated.

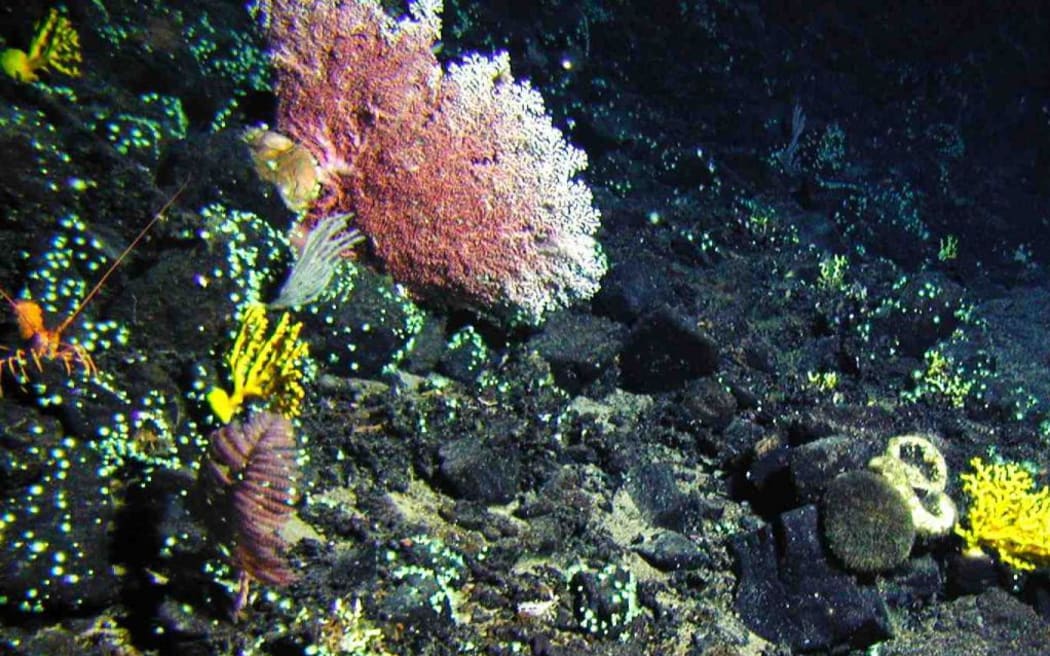

Coral in part of the area that would be covered by the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary. Photo: Malcolm Clarke / NIWA

Announced in 2015 by then-Prime Minister Sir John Key - to much international fanfare – the Kermadec ocean sanctuary was meant to be one of the world's largest marine protected areas.

But last week, the sanctuary hit another major roadblock. After years of negotiations to reach an agreement, Te Ohu Kaimoana – the group representing Māori interests in the marine environment – resoundingly voted against the proposal that was on the table.

Environment Minister David Parker said he was disappointed and now there appears to be no clear way forward.

The Kermadec ocean sanctuary would cover an area twice the size of New Zealand's land mass, and fifty times the size of our largest national park. The 620,000 square kilometre swathe of ocean brushes the northern perimeter of our exclusive economic zone.

"It's a volcanic island chain, so it's got a lot of special minerals, very clear water. It's on the migratory path for a lot of creatures: a lot of whales, dolphins and fish spend their time there," Stuff senior journalist Andrea Vance tells The Detail.

"It's hugely important for the world and for New Zealand's biodiversity."

When the sanctuary was announced, the world applauded.

Vance says there was a big focus on ocean protection at that time, with the Obama administration in the United States bringing oceans to the forefront of environmental policy globally.

However, back home, iwi were blindsided.

"The reason it took Māori by surprise in particular was that there hadn't really been any consultation with Māori about this, particularly with Te Ohu Kaimoana, who have responsibility for developing and protecting Māori interests in fisheries," says Carwyn Jones (Ngāti Kahungunu, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki), pūkenga matua of Māori laws and philosophy at Te Wānanga o Raukawa.

Jones explains the 1992 Fisheries Settlement, an agreement between Māori representatives and the government, which recognised Māori commercial fishing rights – a right guaranteed by Article Two of the Treaty of Waitangi.

"This [sanctuary] proposal was going to cut across those rights, and in fact remove some of those rights, and so was to some extent undermining that settlement that had been agreed to," he says.

Since 2015, progress on the sanctuary has grinded to a halt. Te Ohu Kaimoana launched legal action over the potential breach of the 1992 Fisheries Settlement, and Te Pāti Māori threatened to walk away from its confidence-and-supply arrangement with the National Party. And when the government changed in 2017, there were more obstacles.

"New Zealand First were very opposed to the Kermadec sanctuary. The government then decided that it would quietly behind the scenes consult with Te Ohu Kaimoana and mana whenua," says Vance.

Now, after the recent vote, there are questions over whether it will ever go ahead.

"The government can now choose to go ahead and push through the legislation, even though it doesn't have the support of Te Ohu Kaimoana, which means it will probably end up in court," Vance says.

"Or it can drop the proposal. The problem with that though is it sends a signal that [with] any form of marine protection and ocean sanctuaries and marine reserves – Māori fishing interests have a right of veto – so they basically can say whether they go ahead or not – it sets that precedent.

"That's really of concern to environmental groups - that's because there has been no marine protection in New Zealand for well over a decade because of these issues."

However, Jones says there could be a way forward, with Te Ohu Kaimoana mooting a Māori-led solution.

"If you're adopting a tikanga Māori approach, then at the heart of tikanga is not only our relationships between people, but our relationships between people and the natural world."

Jones points to the Whanganui River settlement as a possible model for what could happen next.

He says there is a need for more environmental protections, "but they need to be undertaken in ways which are effective and recognise the rights that people hold".

Find out more about how the proposal for a Kermadec ocean sanctuary fell apart in the full podcast episode.

Check out how to listen to and follow The Detail here.

You can also stay up-to-date by liking us on Facebook or following us on Twitter.

Photo: