By Justin Rowlatt, Climate editor, BBC News

Greenpeace activists protesting around MV Coco, a specialised vessel collecting data for The Metals Company last year. Photo: Supplied/ Greenpeace / Martin Katz

Greenpeace could be thrown out of the United Nations (UN) body overseeing controversial plans to begin deep-sea mining.

One mining company claims the campaign group disrupted a research expedition in the remote Pacific.

Member states of the UN's International Seabed Association could choose to strip Greenpeace of its observer status within the group.

Greenpeace said the incident in question was a peaceful protest aimed at protecting a pristine ecosystem.

The mining company involved, The Metals Company, accuses Greenpeace of being "anti-science".

It is the latest salvo in a long-running battle over access to a trove of hundreds of billions of dollars' worth of metals lying on the surface of the seabed in some parts of the deep ocean.

Green campaigners said it would cause terrible damage to one of the few remaining ecosystems on Earth untouched by humanity.

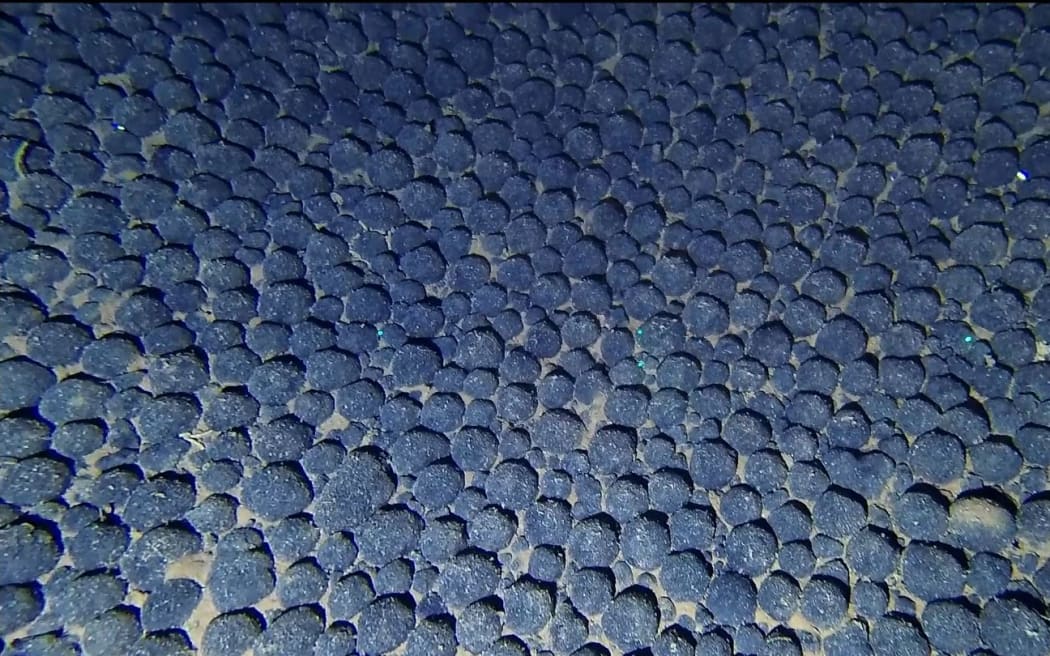

The metals the companies want to exploit have built up over tens of millions of years into potato-sized lumps, known as polymetallic nodules.

Mining companies say the copper, cobalt, nickel and manganese they contain are crucial battery metals.

The International Energy Agency forecasts demand for these metals will soar as the world continues the effort to transition towards a low-carbon economy.

Green campaigners said there were sufficient supplies of the metals on land and no ocean mining should be allowed until the deep-sea environment, and the impact mining would have on it, were much better understood.

Whether action will be taken against Greenpeace will be decided by the representatives of 167 countries at an International Seabed Authority (ISA) meeting this week.

These latest international talks continue an ongoing effort to decide what rules should apply to companies that want to collect minerals from the abyssal plain, one of the deepest parts of the ocean. The ISA has said it aimed to have rules in place by 2025.

Both the mining companies and green activists claim to be acting in the best interests of the planet.

The US has never ratified the international treaty which created the ISA, so plays no active role with the body.

This week, a group of influential US political and military leaders, including Hillary Clinton, called for the US to ratify it, arguing competition with China meant access to deep-sea metals was crucial for the country.

Greenpeace activists protesting around MV Coco, a specialised vessel collecting data for The Metals Company in November 2023. Photo: Supplied / Greenpeace / Martin Katz

The Metals Company said the research trip interrupted by Greenpeace in November was for science which aimed to help improve knowledge of the effect nodule collection would have.

It said the work had been requested by the ISA as part of an impact assessment and that Greenpeace deliberately hampered that effort when its activists boarded the company's research vessel.

For its part, Greenpeace said the action was justified because The Metals Company had said it planned to press ahead with mining before regulations had been agreed.

Mining companies plan to use machines like huge vacuum cleaners to trundle over the seabed, hoovering up the nodules.

The greatest concentration of the nodules is at depths between 4000m and 6000m.

They are found across much of the deep ocean floor.

The Metals Company plans to mine in an area of the Pacific Ocean known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

For years, it was assumed very little could live in these cold, dark and oxygen-poor depths.

A Cook Islands nodule field, taken within the country's exclusive economic zone. Photo: Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority

The density of living things is indeed low, but research over the past few decades has revealed a huge diversity of species, including a great many which are new to science.

But the abyssal plain is vast. It covers 40 percent of the entire surface of the Earth. Land makes up just 29 percent.

"I understand why the greens are cautious," said the chief executive of The Metals Company, Gerard Barron, "but on this occasion, they've got it wrong".

He acknowledged the 75,000 sq km his company planned to mine was big, but said it represented a tiny proportion of the deep seabed.

The Metals Company claimed its research showed while there would be damage in the area where mining took place, the sediment plumes which could suffocate deep-sea creatures would only travel a few miles.

Barron said the question which should be asked was: "Where can we get these metals from with the lightest planetary and human touch?"

Greenpeace rejected the idea deep-sea mining could have any environmental benefits.

"Deep-sea mining is not a climate solution," said the organisation's lead oceans campaigner, Louisa Casson.

"I think it is clear that to protect the climate, we need to be restoring our oceans, protecting them, not destroying them further by adding new pressures."

Greenpeace maintained it was justified in disrupting The Metals Company's research because it was "tick-box science by a company with a commercial interest in the outcomes of that research".

The NORI-D exploration of the Clarion Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean. Photo: The Metals Company

Twenty-four countries, including the UK, have said they support a moratorium on deep-sea mining. They say licensing must wait until sufficient scientific evidence is available to assess the impact and to draw up regulations that protect the deep oceans.

A group of British scientists is currently surveying species on the abyssal plain in the eastern Pacific.

Speaking from the research vessel RRS James Cook, Dr Adrian Glover of the Natural History Museum told the BBC he supported the regulatory process the UN had put in place.

"It is a new industry and we should be concerned and we should ask difficult questions," Dr Glover said.

He said research must continue to assess the risks of mining.

"There's always a risk with these things and collecting data and collecting evidence is the way to reduce that risk to understand what it is, and then ultimately to make a decision."

The great advantage the world had as it decided how to proceed with mining on the abyssal plain was that regulation was being made before the industry had started, Dr Glover said.

"It is up to the international process, the regulatory process to assess the evidence critically … and ultimately decide whether it is acceptable or not."

- This story was first published by the BBC.