If we place women at the centre of our account of China’s past two centuries, how does this change our understanding of what happened? - historian Gail Hershatter

A scene from The Red Detachment of Women. Photo: Supplied

“Women hold up half the sky” Mao Zedong is famously quoted as saying. But according to Gail Hershatter, he never said that.

The quote first appeared in the People’s Daily newspaper in 1956 and was actually “Women can hold up half the sky” – more a statement of potential rather than a fact, Hershatter points out.

In her new book Women and China’s Revolutions, Hershatter looks at just how heavy this 'half the sky' was for the Chinese women tasked with holding it up over the last 150 years.

Women in China’s long revolutionary century - from the uprisings which fatally wounded the Qing dynasty to the Nationalists and then the Communist Revolution and finally Deng’s market reforms - suffered tremendous hardships, but also forged new roles for themselves.

Hershatter opens her book by asking what the revolutions were like for women in China.

“Women had revolutions but they did not have exactly the same revolutions as men” she concludes.

Ding Ling, Chinese feminist activist and writer Photo: Supplied

You can feel the weight of scholarship in Women and China’s Revolutions, but Hershatter never gets weighed down by it.

It seems to be a summing up of her years of academic work into Chinese women.

Hershatter has written oral histories of rural women in China’s interior under Mao, studied how market reforms affected women in the 1980s, written histories of prostitution in Shanghai and on the lives of workers in industrial cities after the fall of imperial China in 1911.

She is also a past president of the Association for Asian Studies and Distinguished Professor of History at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Hershatter is able to interpret the broad sweeps of Chinese history and then swoop down to village level or into factories to tell the stories of ordinary women trying to make sense of the revolutions, carve out new lives or just survive.

Her cast of characters is broad.

There are the Red Lanterns, young village girls aged up to 18, who formed military units to fight alongside the men in the Boxer rebellions of the early 1900s and were believed to be able to fly, stop the enemies’ guns and bring the dead to life.

There’s revolutionary Tang Qunying, described as being adept at “bomb-making, poetry, battlefield tactics and public speaking", who also delivered the most famous slap in Chinese history.

Tang Qunying walked on stage at a convention of Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist Party and slapped her male political associate Song Jiaren with her fan after he traded away women’s suffrage to keep peace with the Conservative wing.

Then there's the writer Ding Ling who was with Mao and the Communists in their wartime bolthole of Yan’an and wrote about the gulf between the rhetoric of Communism and some of the cadres’ real behaviour, especially casting off their old wives and taking new partners.

This hit a nerve, says Hershatter.

Mao had just divorced his wife who accompanied him on the Long March and bore five children, sent her to the Soviet Union for treatment for depression and married a former Shanghai film actress.

Ding Ling was denounced, her work repudiated in the Communist press, her editorial positions removed and she was dispatched for two years to the country to learn the ways of peasants.

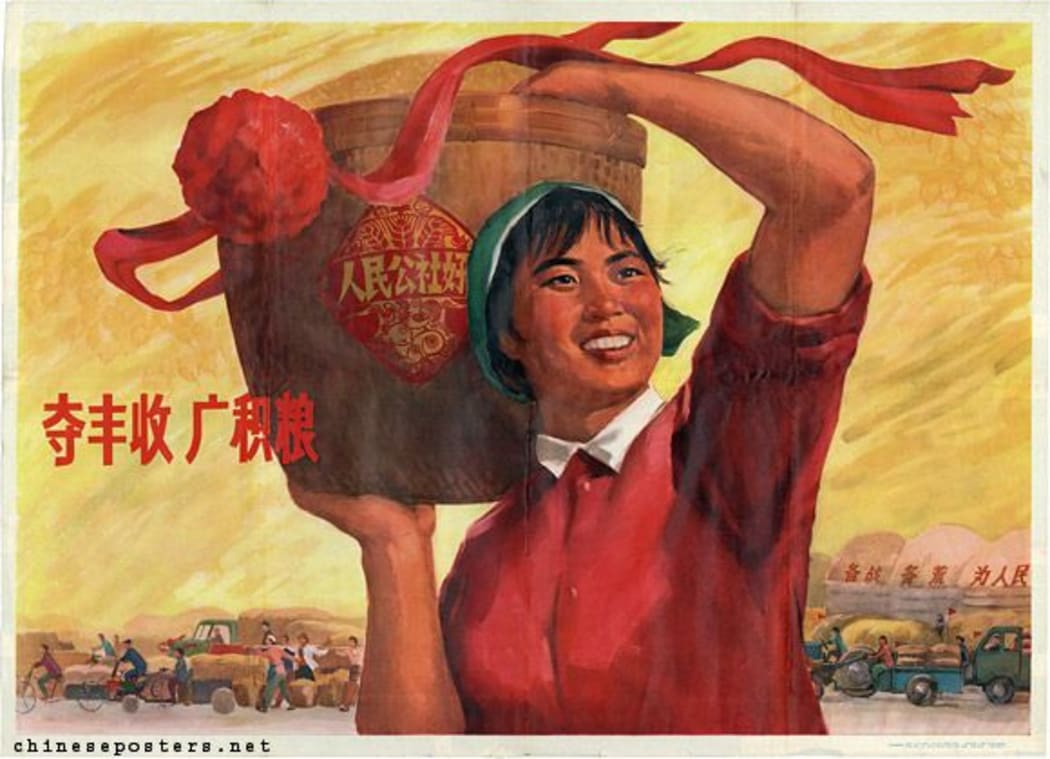

Bringing home the harvest poster Photo: Supplied

One of the most revealing chapters centres on the very different lives of city women and their village counterparts.

When the Japanese armies invaded and swept down the eastern seaboard, many city women, some students, fled to the Nationalist capital inland at Chongqing and were then dispatched to the countryside to teach in rural schools.

People would line up for hours to watch these alien creatures walk to work, studying their clothes and their gait.

Hershatter is best, though, when she maps out how the lives of urban and rural women differed and, more importantly, how their lives were affected by the shifting policies of first the last Emperor, then the Nationalists, the Japanese invaders and, finally, the Communists under Mao and then market reformer Deng.

Hardships and Heroes

The last 150 years of Chinese history has been punctuated by famines, war and opium and there is no doubt life during this period could be terribly, terribly hard.

Hershatter sets out the desperate poverty and grinding violence as more and more men (and some women) became addicted to the opium washing through the country under the Qing.

Addicts would sell their daughters or their wives to buy more.

There was little money left for food. Famine was a constant spectre.

One eyewitness recounted bodies piled beside roads, filled with cartloads of women fleeing from a famine in north China during the Boxer Rebellion of the 1900s or else being sold to men in the south.

Wars and rebellions brought threats of rape and sexual violence.

A new book explores women's lives in modern China Photo: Supplied

Bandits, warlord armies, the ill-disciplined armies of Chiang Kai-shek and then the Japanese war machine (“the Rape of Nanjing, a name that should be understood literally,” says Hershatter) all brought terrors.

In one harrowing story, a villager recounts hiding in a tunnel from Japanese soldiers when a baby began to cry. She was smothered by her mother rather than give away their hiding place.

Aside from the grimness, Hershatter’s main message is the way Chinese women tried to carve out a better place for themselves as society shifted massively, the country industrialised and then grew wealthier.

The practices inflicted on (and by) women were considered feudal by reformers, from footbinding to arranged marriages and then the difficulty of divorce.

Modern reformers, from the people who opposed the Qing to the Nationalists, the New Culture movement and the Communists, were all committed in their own way to lifting up women.

But, as Hershatter points out, they were often male and misunderstood women’s lives. Some belittled or ignored centuries of female history, craftworks and arts.

Then there was the difficulty of shifting the attitudes of peasants, men and women when a woman’s labour was so vital to the survival of the household.

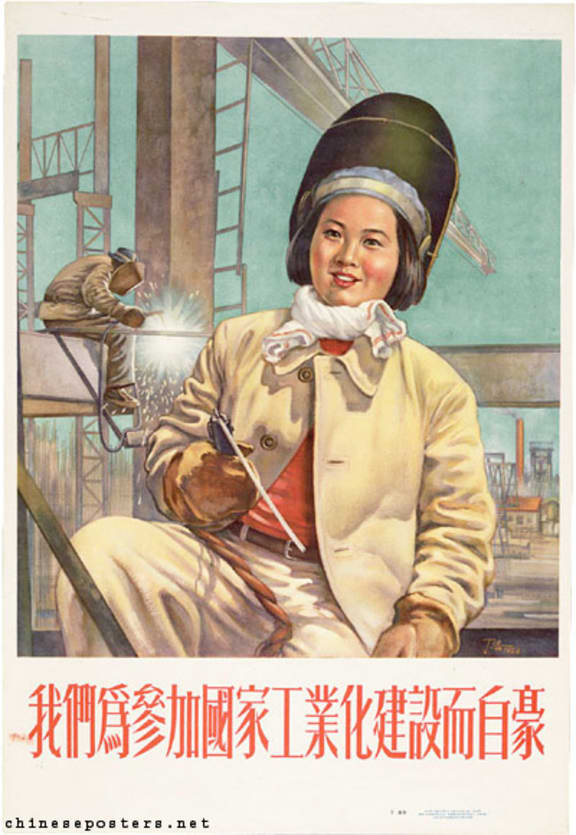

Women were encouraged to be part of industrial work Photo: Supplied

Reformers saw women in the abstract as being held back by feudal attitudes, born into servitude and obstructed by Confucian expectations, especially in rural areas.

If they could be liberated then they could be educated, employed and free to choose their spouses. Households would be stronger, the economy better served and the State enhanced.

Women could be the builders of a new China. Many women did begin to carve out new opportunities, says Hershatter.

They insisted on free choice in marriage, or took advantage of divorce laws to escape brutal, unloving partnerships, or found new roles in an industrialising China.

But Hershatter is especially strong in depicting how the hopes of, often male, reformers foundered in conservative rural areas, did little to help women or even hurt the people they wanted to save.

One example is the Great Leap Forward when rural women took to heart Mao’s exhortations to build a new socialist economy.

Women were extolled for embracing the new farming collectives, for their work in the fields, for working long, long hours to produce more crops, for finding new production techniques, for taking on night-time shifts to grow more crops, having worked all day.

These were all counted by the Communist Party as productive work. But all the work of raising children, cooking, cleaning, caring for relatives or producing handicrafts to sell, were not counted by the Party as labour since it occurred outside the collective.

None of it was remunerated. Women building a new China were working double shifts but getting less reward from the collective.

A wedding in Shanghai Photo: Supplied/ Jeremy Rees

Ongoing Struggles

Struggles persist today. In the Reform era, China has become a nation of homeowners but married women are disadvantaged by the law around who owns a house.

Overwhelmingly, the man’s name appears on the deed, so any divorce settlement skews to the husband, a fact upheld by Marriage Laws and Supreme Court rulings. Writes Hershatter:

“In buying a home for a new couple it was customary, following long-standing marriage practices, for a man’s family to finance part or all of the purchase of the structure, whereas a woman and her family took responsibility for internal walls, fixtures, paint and appliances. In popular understanding, the man was buying the house, even when the internal construction was extremely expensive.”

This all became an issue when China’s Supreme Court ruled that purchases before a marriage - like providing funds for a house - remained the property of one partner alone.

In a divorce, a wife could find herself without a share of the couple’s main share of wealth.

“A law that on its face was gender neutral had profoundly gendered effects,” notes Hershatter.

Women and China’s Revolutions is a book which deserves a wider readership than it may find.

Hershatter knows her subject and is able to bring it alive with anecdotes, characters and insights that keep you reading. And while she grapples with the sweep of China’s revolutions,

At the heart of her book, she places ordinary women doing extraordinary things

“If we place women at the centre of our account of China’s past two centuries, how does this change our understanding of what happened?” Hershatter asks in her opening pages.

The answer from Women and China’s Revolutions is – profoundly.