What is it with some murders? There are killings which haunt us; Lundy, Bain, Thomas or Watson. Historic cold cases tantalise; justice denied, an ending delayed, the killer at large, a puzzle perpetually in pieces.

Pamela Werner in one of the last known photos of her. Photo: Supplied

The death of Pamela Werner seems to be one. The 20-year-old college student, was murdered and dumped below the old walls of Beijing on a cold night in 1937. The killing filled the city’s foreign community, already on edge over the growing Japanese army to the north, with dread. She had been mutilated. Someone had slashed at her over and over again, broken her ribs outward with great force and cut out her heart. The murder has never been solved. It has spawned two very good and very different books.

Paul French’s Midnight in Peking, subtitled how the murder of a young Englishwoman haunted the last days of old China, was the first published, in 2012. A writer and businessman in Shanghai, he’d come across the story in a footnote in Edgar Snow’s account of the rise of Mao’s communists, Red Star over China. Snow and his wife, Helen, lived close to Pamela and her foster-father and Snow mentions how fearful and upset she had been at the killing. French’s book was an immediate success. It spent weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. It won the Crime Writers Dagger for best non-fiction and the Edgar award for best factual crime book. Rana Mitter, one of the best historians of 20th Century China and an expert on the period, called it “spellbinding” in his review for the Guardian. The New York Times called it an “excellent account”. There have been reports that the producer of TV’s Sherlock Holmes and Spooks is interested in making a mini-series.

Pamela Werner in a photo taken on a trip outside Beijing Photo: Supplied

Except, says Graeme Sheppard, a former Scotland Yard detective turned writer, French got it wrong. (It is one of the great benefits of decades-old cold cases that writers can disagree without upsetting anyone). Sheppard’s account, A Death in Peking, is the result; released this year, it too is very good. He came across the case because his wife’s grandfather had been a British consul in China at the time and gave him French’s book. He became uneasy, then decided to investigate for himself. “The Midnight in Peking account was, to me, unfair and inaccurate in its analysis and incorrect in its conclusions,’ he writes. “It purports to be history but is not.”

Differing accounts

A Death in Peking by Graeme Sheppard Photo: Supplied

The two accounts couldn’t be more different. French’s account is cinematic, his city teeming with characters. Ancient evil stalks old Peking; the colonial section is filled with the mad, depraved, twisted or corrupt. The murder is committed under the Fox Tower, a place reputed to be haunted and where old ghouls of fox spirits emerge. French calls his book a “reconstruction” to fill in the blanks. When the Chinese police inspector, Han Shi-chung, walks to the murder scene, French takes us through the clamouring hutongs, out onto the packed main streets, through the guarded old gates at the northern corner of the consular Legation section, up onto the old walls of Peking, past the Fox tower where a white Russian had committed suicide by cutting his own throat with a razor, through the haunted section where restless spirits were said to attack the living, pauses to look out over the “Badlands” where the dives, brothels and seedy pleasure palaces sit jumbled together, and finally to the body. Sheppard notes the time he arrived.

The death of Pamela Werner came at a particularly difficult time for the Western community in colonial-era Peking. The Japanese were massing in Manchuria, waiting for a reason to strike south; it came a few months later in the Marco Polo Bridge incident. The Nationalist government had packed up from Peking and headed south to Nanjing to get away from the Japanese. The Civil War with the Communists was still ongoing. The Western Legations with their consular officials, walled off community and jazz clubs, were emptying out. Both books are good on the dread in old Peking.

Equally admirable is that Sheppard and French have time for the Chinese characters, like Detective Han and the others. They come across as hard-working, industrious and trying to carry on amidst the growing chaos of China. In fact, it is the Westerners who seem exotic and mad - a nice inversion of many books on China.

The murder cast

The murder dropped into the middle of a cast of characters which, in a movie, would be considered contrived. There is a hint of Agatha Christie in the assemblage. There was Wentworth Prentice, the American dentist to Pamela whose wife had suddenly taken the children and fled China. He also happened to run a nudist club in an abandoned temple outside Beijing, says French. There were the two British consuls, struggling to overcome the trauma of being imprisoned during World War 1. And Ugo Cappuzzo, a Mussolini-supporting Italian doctor who managed to overcome typhus plague in villages around Peking by injecting himself with a vaccine made from fleas.

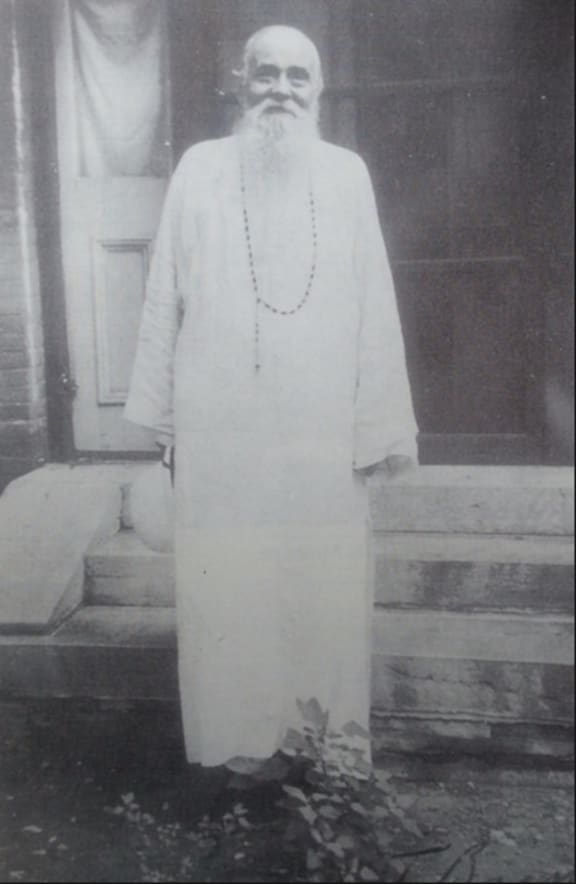

Sir Edmund Backhouse Photo: Supplied

Then there is Sir Edmund Backhouse, a brilliant linguist, an extraordinary Chinese scholar and a fraud. The photos in Sheppard’s book make him look like Saruman as imagined by Christopher Lee in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, all flowing robes, a long beard, fierce intelligence and sad eyes. Sir Edmund published a diary purporting to be that of a very high-ranking official at court. It was a fake. He wrote a memoir claiming to have slept with Oscar Wilde, the Empress Dowager Cixi, the poet Verlaine and an Ottoman princess, some of which was demonstrably untrue. He acted as the agent for companies wishing to sell warships to China. No orders materialised. But he appears in Pamela Werner’s story because he developed an alternative theory taken seriously by the British authorities for a time. He told them that he had heard from an informant the murder was a revenge killing against the British for acquitting two soldiers arrested for killing a Japanese. The problem with this theory, says Sheppard, is that no-one in the British consulate had suspected it was a revenge killing by the Japanese until Backhouse suggested it - and what good is a political revenge murder if no-one knows.

So how is that given the same set of facts that French and Sheppard can diverge so markedly? The answer is in their view of Pamela’s father, Edward Werner, 72 at the time of her death and, quite possibly, the oddest of all the odd characters. He had been born to British and Prussian parents on board a ship in Dunedin harbour, hence his full name Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner. He joined the British consular system in China, rose to be a consul and, depending on one's view, was either a rather disagreeable man or alternatively the most disagreeable man in all China.

Werner: The New Zealand-born foster father

Neither French nor Sheppard seriously think he murdered and dismembered his foster daughter; nor did anyone much at the time, bar the bored, the vicious or the drunk. But they have very different views of him as a truthful narrator. French believes him. Sheppard discounts him. This sets their stories down two very different paths. Social scientists call the effect, path dependence. Whatever decision you made at the first question - whether to turn left or right at the first crossroads, for example - will determine all your other choices from then on. So, French and Sheppard have the same mad cast of characters, the same terrible murder, the same victim, the same brewing sense of dread at impending war, the same tense Peking setting, but arrive at completely different conclusions - and very different books.

1930s Peking Photo: Supplied

Werner believed the police were not doing a good job so paid local scouts for information. He wrote voluminous reports and sent them to the consulate, the British foreign office and MPs. Most of his reports have survived the war in China; most police reports haven’t. Werner came to the conclusion that the killers were the nudist-loving dentist Prentice, a shady ex-Marine Knauf who seems to have spent more time than was good for him running bad bars and the fascist Italian doctor Cappuzzo. They were all deviants, in Werner’s thinking. They were up to no good, frequenters of the Badlands, seducers of innocent young women and, finally, capable of killing to cover up their foul deeds. In Werner’s view, poor Pamela had been seduced by Prentice, taken drunk to a bar, then repeatedly raped by his friends, killed when she stood up to them and disembowelled to make it easier to get rid of the body. They all loved hunting so they were used to dismembering things. The fact that no-one would listen to him was because the American, British and Italian legations were incompetent and protecting their own. An alternative view was that no-one was listening because he was wrong or intensely disliked.

Evidence or opinion?

The problem, says Sheppard, the cop, is that none of Werner’s reports are evidence. At best, he developed a theory. At worst, the reports are the sad, obsessive rantings of a grief-stricken old man. The issue, Sheppard argues, is that French has taken Werner’s reports and used them as the basis for his book. In effect, he has taken the old man at his word and hared off into the Badlands using the writings as fact. Sheppard writes; “It quickly became clear that the Werner reports were in no way objective and were written by a man possessing a strange mind...For the large part, they were little more than rants.”

Detective turned author Graeme Sheppard Photo: Supplied

In French’s telling, Werner is a somewhat unlikeable man but an expert on China after years in the British service and likely to be telling the truth. In Sheppard’s view, he is a paranoid personality; out of his depth as a consul, paranoid about his colleagues and a liar who would besmirch anyone to be seen in the right. Apparently, just two diplomats were ever sacked from the British service in China in 100 years (the clubby, collegial service generally packed incompetents off home as “suffering illness”) and Werner, depending on your count, was either number two or would have been number three, except it was decided to quietly pension him off. He had married late a beautiful woman half his age, who it was rumoured among the snobbish elites was the result of her high-ranking father’s liaison in India with an Indian woman. Werner was driven to distraction, thinking the small Western community in China were gossiping about her, shunning her or trying to sleep with her. In the end, she seems to have withered in China and died young, leaving him alone, friendless, alienated, embittered and with a daughter to raise.

The facts, ma'am

Midnight in Peking by Paul French Photo: Supplied

Sheppard runs through the pages and pages of Werner’s reports trying to extract the facts. He is a “Just the facts, Ma’am” writer. Nothing he turns up seems to prove the presence of a gang of murdering sexual sadists. The British consulate seems to have listened to Werner’s theories politely but done little. Similarly the police, both the hard-working Chinese detectives and the ex-Scotland Yard detectives working the case for the British. Few of their files have survived. But reports of what they were doing and snatches of conversations recorded in minutes seem to show they were focused on a much more prosaic angle - ex-boyfriends. Werner had apparently confronted an ex-boyfriend for stalking Pamela, they got into a confrontation and Werner hit the young man, breaking his nose. The student seems to have vowed revenge. To reveal any more would ruin Sheppard’s investigation.

The outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war saw files destroyed, people detained or scattered. Civil War after 1945 and the eventual victory of the Communists completed the process. Sheppard is very good on the terrible aftermath of these events. Whereas, French tends to follow Werner’s investigations down into the Badland bars and brothels, then stay there, Sheppard follows his characters through the years of war, imprisonment and death. One of his most astonishing findings is that Werner and the men he accused of killing Pamela ended up in the same Japanese internment camp. The old man would shake his finger and hiss at the men that he knew what they’d done. For Werner (if he was correct) and the men (if he was wrong), it must have been a terrible psychological burden even in the midst of a Japanese camp.

Sheppard's view

The Fox Tower, long considered a haunted area Photo: Supplied

So is Sheppard’s A Death in Peking any good? Yes, it is, surprisingly good. It is fascinating as an example of a “reply” book - an author setting out to debunk another’s theory. His argument that Werner got it wrong and that French blindly followed him seems plausible. But Sheppard never forgets he is telling his own tale to readers unaware of what went before. A new reader can start from scratch. He fleshes out his story with lively detail. It is crisply, deftly even, written. He has a cop’s eye for fact and a good writer’s eye for telling details. He can sketch a character with a few choice lines. In the end, his story is less cinematic than French’s account; more Broadchurch to French’s Twin Peaks, but all the better for that. And, as you’d expect, meticulously footnoted, facts cross-checked and gaps noted. Sheppard is a good bet to put your money on who is most likely to get the killing of Pamela Werner right.

Perhaps the one gap in these books is Pamela. She near comes clearly into view, caught somewhere between a teen tear-away, a naive student and an increasingly confident young woman. Sheppard, especially, never evokes her spirit. Today her sad story lives on a little in these books and as a stop on audio-tours of old Peking for tourists. Gone is the world she grew up in of Old Peking with its colonial-era Foreign Legations. Too much time has passed to solve Pamela’s murder; her killer is likely dead. Too many cataclysms have wracked China in the years since. Pamela’s grave has been removed to make way for new buildings. Much else has been torn down, covered over, remade. But the old Fox Tower near where her body was found remains. These days it is filled with a contemporary Chinese art gallery. The area, though, is still considered haunted.