As a young single mother in Arkansas with no medical training, Ruth Coker Burks cared for around 1000 men dying from AIDS through their final days.

This was in the 1980s and 90s when the disease carried such a stigma that patients were shunned by their own families and neglected by the medical profession at large.

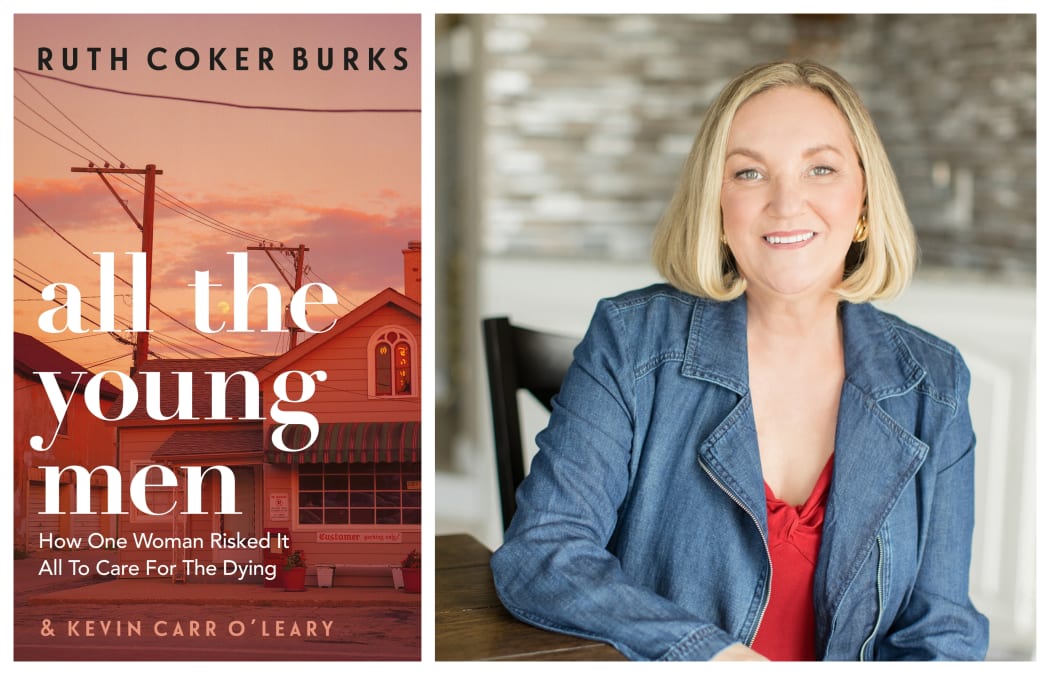

She tells the incredible story in her book All the Young Men: How One Woman Risked It All To Care for the Dying.

Ruth Coker Burks Photo: supplied

Burks tells Kim Hill she first became involved in caring for men with AIDS when she was helping a friend going through surgery for cancer at hospital.

“I looked over at this door that they’d just put this big red tarp on, and it said ‘biohazard’ and ‘do not enter’ and I was wondering what was up with the door. Then the nurses started drawing straws to see who would go in and check on the patient.

“It was just unbelievable what was happening. That young man in there had what they called ‘that gay cancer’ and they didn’t want to go in and check on him, they were turning their backs on this young man, it was just awful.”

Burks waited until the nurses had gone to the other end of the hallway then sneaked into the room to check on the man.

“I asked him, is there anything I can do for you, and he said he wanted his momma. I thought, I can do that."

She went and told the nurses that the man wanted to see his mother and they were incredulous she had entered the room.

“They just backed up like I’d grown three heads or something and one of them said, honey, his momma's not coming, nobody's coming, he’s been here six weeks and nobody's coming and don’t you go back in that room.

“I thought, this isn’t right. I knew it was that gay disease, whatever that meant. I finally got his mother’s phone number wrangled out of them and I reached for the phone on their desk that I’d been using for the past five years, and they pulled it away. I looked at them and I knew what that was all about. They said, the pay phone is down the hall and I thought, oh my gosh, I can’t believe y’all are going to be that ugly about it.”

Burks says she didn’t feel she was different to her peers or community, but she believed in her church’s teaching that people should care for the poor, sick and needy – and she was surprised other people weren’t doing the same.

“I thought I heard the same sermons that everybody else was hearing.”

Ironically, after she began caring for men with AIDS, her church shunned her.

“I was so stupid or naïve, or maybe both, or maybe God had put blinders on me so I couldn’t see what was happening, but I didn’t realise they were shunning us. I just kept trying so hard to fit in.”

Due to an argument between her mother and uncle, Burks mother bought up every remaining space at a local cemetery so that he and his family couldn’t be buried with hers.

“She put up her own monument that said ‘woe be on to you hypocrites, pharisees and scribes’ and said that was for Uncle Fred.”

Burks inherited 260 spaces and, when young men died of AIDS, she would smuggle their ashes into the graves.

“The first ones I did at night where no one would really notice me, and it might just look like I was there praying. I did that, and no one ever found out.”

She would often contact families of the young men, but almost always they weren’t interested in hearing about their sons or visiting them.

“It was almost like they were reading a script. They didn’t even want a call when they died, they didn’t want to know anything.”

Burks kept all her work a secret until her ex-husband died in 1986 because she was convinced she would lose custody of her daughter if it came out.

“There wasn’t a judge alive who wouldn’t have taken her away and given her custody to her daddy or anybody but me.”

She says that, far from being morose about having AIDS, the young men with her lived every day to its fullest and were convinced that a vaccine or cure was just around the corner.

“They would take their AZT [AIDS medication] until the day they died because they just knew the day after tomorrow, there would be a cure.”

Burks’ father died when she was young and her mother was abusive and difficult. Her marriage was also difficult. She says that, in a way, the young men gave her a family she hadn’t had before.

“My UK editor said the book was a love letter to my men, and it really is.”

Along with caring for men, Burks would go to gay clubs to do outreach on protective sex and would do HIV blood tests for young men. She says Arkansas had made it illegal to do anonymous testing for HIV, but she realised there was no penalty for it.

“I thought, that’s fine, so I’d send it in with Nancy and Ronald Reagan’s names who’d completely ignored that AIDS pandemic and let it become what it is today. The director of the health department called me, just screaming at me saying, how dare you put Ronald and Nancy Reagan down, I don’t wanna see their names and birthday’s down again.”

Following that, she put her own name down and every test and he called again saying he didn’t want to see her name on anymore tests.

“So, the next week, I put his name and social security number down and, when he called, I said how do you want it? I’m gonna test these people and this is the only way they’re going to get tested and you know that as a gay man, so you just tell me how you want it, your name every time, or Nancy Reagan every time. He knew he couldn’t do anything.”

With life-extending and life-saving drugs being introduced, Burks says she’s thankfully no longer needed to care of these men. Today, she’s planning a memorial for the cemetery where she buried so many of the men and says she looks back on the time with pride.

“I’m very proud of what I did and I’m very proud of my men and how gallant they were.”