Those coins jangling in your pocket or the numbers on the ATM screen are part of the greatest fiction ever created.

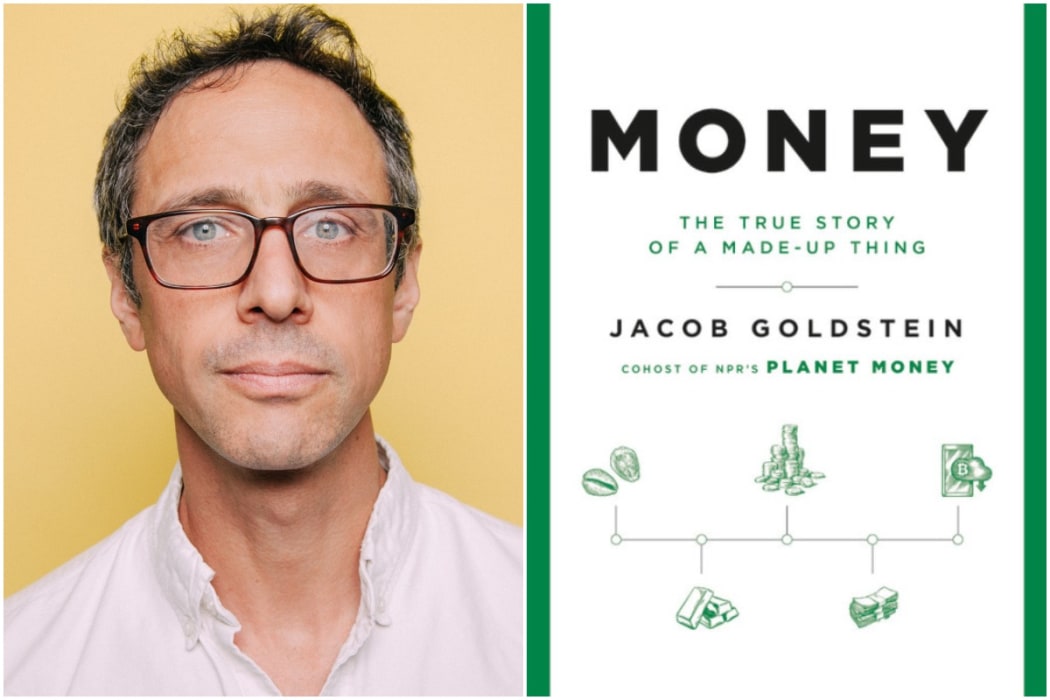

That's how Jacob Goldstein thinks of money.

It's only worth something only because we all agree that it is. He's the co-host the popular Planet Money podcast.

Photo: Supplied

He explains how it all adds up in his book, Money: The True Story Of A Made-Up Thing.

Goldstein tells Summer Times his interest in money came later in life.

“I spent most of my life not thinking about/avoiding money. I studied English in college and then, in 2008, we had a financial crisis so I sort of had to think about it, like a lot of other people.”

He says he was out at dinner with his aunt, a successful businesswoman, and he asked her where all the trillions of dollars had gone. She told him that money was fiction.

“It was never really there in the first place. So, that was the beginning, that’s where it started.”

Goldstein says money exists because we all agree upon a set of rules that make it so.

“If we don’t, if there’s some critical mass of disagreement, then it doesn’t work – it’s not money.”

In the 1800s, Goldstein says, every American bank printed its own version of paper money, which was basically a claim check for precious metals.

“There were thousands of banks in America and thousands of kinds of paper money, which is mind boggling and delightful. Merchants and store owners had to subscribe to certain publications that explained what every single bill looked like, including ones with Santa Claus on it, ones with whales on it… and it would tell the merchant whether they should accept the money at full face value.

“If a bank was shady or about to go bankrupt, it would say don’t take the bill at full face value, apply a discount to it because you might not be able to get the silver or gold coins for the piece of paper.”

There’s a romantic idea that before money came along, the economy worked through bartering goods. However, Goldstein says, modern anthropology has shown it was never the case.

“What they’ve found instead was, in many ways, more interesting. They found that traditional societies – societies that are largely self-sufficient and built on webs of kinship – they have lots of norms and informal rules about reciprocity and gift giving… the current thinking is that the roots of money lie in those very social norms and rules, much more than any imagined bartering world.”

Goldstein says China was one of the first places to use paper money, which were typically claims to bronze coins. It was when Kublai Khan and the Mongols invaded China that paper money was recognised as a very efficient to move value around.

“Eventually Kublai Khan says it’s not going to be a receipt for bronze anymore, the paper itself is just going to be money and it worked and the Chinese economy, for a while, ran on paper money.”

After the Mongols were repelled from China, the Ming Dynasty took a reactionary view and did not look favourably upon paper money.

“They actually got rid of paper money and paper money disappeared from the world entirely for a long time, until it finally reappeared in Europe quite a lot later.”

Until 1933, most modern economies were on the so-called “gold standard” where paper money was tied to the value of gold and technically exchangeable. Instead, money returned to the Kublai Khan model of having value in itself.

“It was a good move. The Great Depression was caused or, at least, made much worse by the gold standard. You had falling prices and people defaulting on their debts. What you really needed was actually more money floating around in the world – not more wealth but more money itself.

“Going off the gold standard allowed countries to do that and made things start to get better. That is the world, really, that we’re still living in.”

He says that if countries couldn’t print money in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, it would be much more likely we’d have fallen into major depressions.