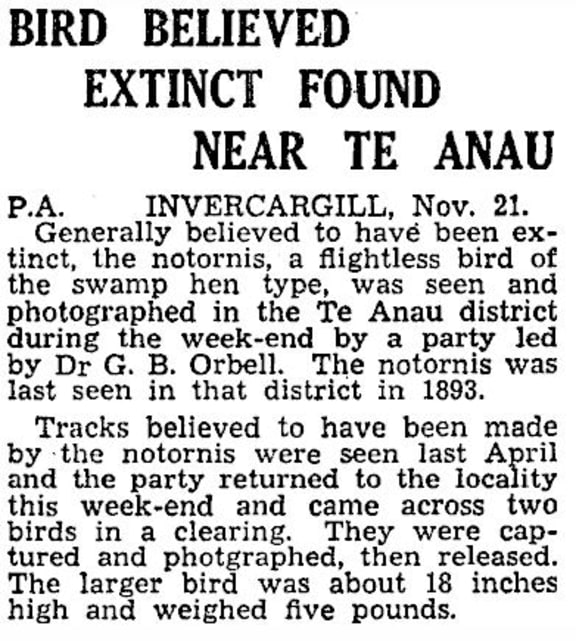

In November 1948, Invercargill doctor Geoffrey Orbell discovered two pair of South Island takahē living in a high valley in the Murchison Mountains of Fiordland. The birds had not been seen for 50 years and were presumed to be extinct.

In this week's visit to the sound archives of Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision we hear recordings about the rediscovery, and how a secret operation helped bring takahē back from the brink of extinction.

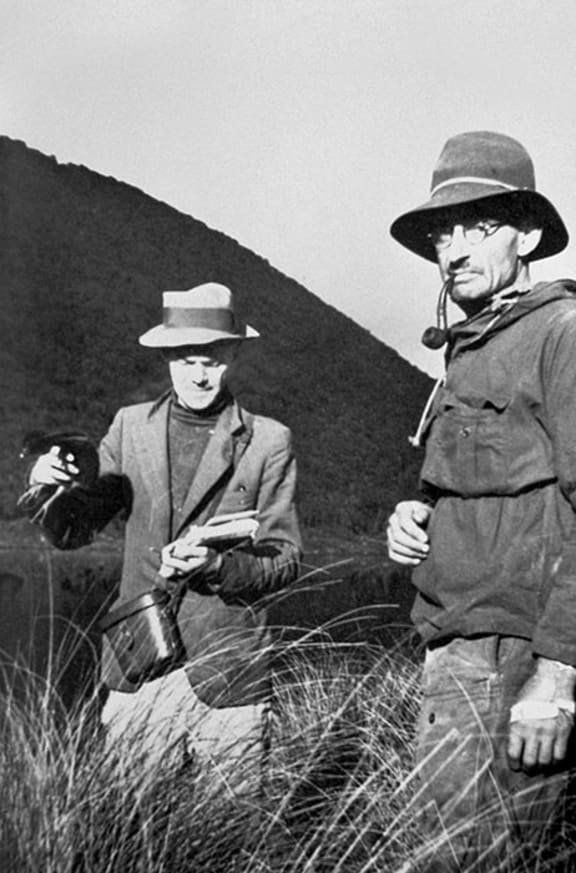

Dr Orbell who liked deer stalking and tramping came across these birds on one of his tramps.

The discovery captured public interest, both here and overseas - but this was in an era before conservation and the importance of preserving the natural world were widely appreciated.

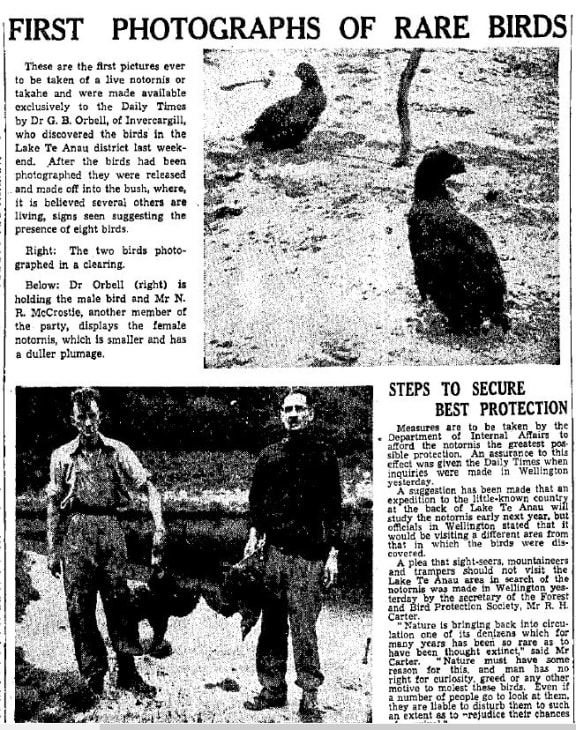

"You can imagine the headlines today if an extinct bird such as the huia was rediscovered – but in the Otago Daily Times in 1948, there was initially just a modest two little paragraphs, followed a couple of days later by a photo and a bit more publicity," Sarah Johnston from Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision told Jesse Mulligan.

She couldn't find any evidence that Dr Orbell was interviewed for the radio on his discovery in 1948 – but excitement did build because in January in 1949, a second expedition was made into the remote region to look for more birds .

This time, Jack Sorensen, a naturalist and founder of the Southland Museum went along with Dr Orbell, and also Dr Robert Falla from the Dominion Museum – now Te Papa.

Jack Sorensen was interviewed for local radio, and he was quite the good storyteller.

"A cool and dull morning saw our party join the launch at Te Anau at 6am for the journey along the lake to where we would enter the forest on the west side. We were a cheerful and slightly excited band and there was much good-natured char concerning the size of packs and individual tastes in clothing.

“The journey along the lake was made in good time and soon we were ashore and adjusting packs in preparation for the climb which was reputed to take about four hours.

“The balance of the stores was distributed and owing to the attacks of myriads of sand flies and mosquitoes no time was lost in getting underway.

"At last we were in takahē country. Many people have asked me my impressions of this isolated valley and to all my reply has been the same; it was just like being in another world. If one of New Zealand’s long-extinct giant moas had walked out of the forest I would have been interested but hardly surprised.

"Of course all hands were keen to start the search for the birds, but Dr Orbell, who was in charge of the expedition, decided that it was important that the birds be not disturbed unduly and the serious workers should have first chance. And so Dr Orbell, Dr Falla, director of the Dominion Museum and I went towards the lakeside in the evening light.

“Success greeted us almost immediately and several birds were seen and, what we had not expected, a number of nests were found. Slowly we converged to within two feet and then out sprang the bird away from us and, to our intense surprise, out our side came a chick. This we captured, although being so close, so excited and getting in one anothers' road, we almost lost it in the tall tussock.

“And then occurred one of the most delightful incidences I’ve had in all my studies of birds, the parent bird reappeared attracted by the shrill cheeping of the chick and circled us at close range. Maternal solicitude having overcome all fear and caution, this gave us the opportunity to take many pictures - both still and movie.

“Because this was the first takahē chick ever seen, at least by white men, we took it back to the camp partly to show the others and mainly to obtain measurements and sketches; we reasoned that the parent bird would not desert the locality.

“When we released the chick the parent bird came back, and all hands were given a really close look at an adult takahē. Those that might have doubted hitherto the peacock blues and greens of the plumage, together with the vivid red beak seen on the single New Zealand museum specimen and reproductions were satisfied. The bird was even more glorious in life, cameras clicked and movie machines whirred, notes were taken and an excited buzz of conversation heard all round.

“We then proceeded up the valley, we saw many more adult birds and counted nests both fresh and old. Slowly our knowledge piled up and then came another thrill we had not dared to hope for, and it seemed only fit and proper that our genial leader should make it, he flushed one bird off a nest in the bases of tall tussocks and there was an egg. A pinky-stone colour and with dark and light brown, brownish blotches all over it. The first takahē egg ever beheld.

“We ascertained that the takahē lived in the area in good numbers, but it required a certain kind of country and was unlikely to be found far from it, that it existed in a neighbouring valley, and that if unmolested it would continue to survive in this isolated and mountain vastness and that far from being extinct, the takahē was still a living member of New Zealand’s queer bird fauna.”

Following their rediscovery, experts believed takahē were at first safest left alone in the mountains, Sarah says.

However, in 1957 it was decided to try and breed some birds in captivity. This was a highly secretive operation as the Wildlife Service (as DOC was called in those days) didn’t want the public to swamp the property where the birds were being raised.

This was in northern Wairarapa in what was to become the Mt Bruce Wildlife Centre – now the Pūkaha National Wildlife Centre. The reason the chicks were taken here, was it was on a property owned by an extraordinary man named Elwyn Welch. He was a farmer who had a passion for wildlife and had hand-raised other endangered birds.

In a secret operation, he trained some bantam hens to raise pūkeko chicks, which are related to takahē – then he and the bantams were flown to Fiordland, under an assumed name – and the chicks flown back with the bantams to his property to be raised by their new mums.

This was a success - and in 1960, the project was announced to the public and over 13,000 people visited his property in 3 weeks to see takahē for the first time.

In an interview from that era, Dr Orbell was optimistic the birds would survive in their native habitat.

“I think the birds will continue to live in that area provided it’s left alone by interfering outsiders and is handled by the internal affairs department then I think that it will survive very well.”

Dr Orbell was asked at the time about the prospects for nature tourism in New Zealand, and despite the female interviewer’s doubts about the interest in wildlife, he was optimistic and predicted big things for conservation tourism in New Zealand.

Photo: Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision