Last weekend marked the 75th anniversary of the arrival in New Zealand of around 800 Polish child refugees during World War II. Commemorations were held at Pahīatua, the site of the camp which was home to the children in 1944.

The Polish children were victims of the Soviet Union's 1939 invasion of eastern Poland. About 1.5 million Polish people were deported by the Soviets, including whole families who were exiled to Siberia. Many of the children came from educated families, with parents who were teachers, doctors or academics, as they were targeted by the invading Soviet Army.

The families were transported across Russia in cattle wagons for three weeks, to work on Siberian collective farms.

In 1975, several of the former child refugees, now adults, were interviewed about their experiences for RNZ’s Spectrum programme.

These women remembered as well as enduring terribly harsh conditions, their parents were constantly interrogated by the Soviet authorities.

“I do remember my mother she was constantly called for the questioning, the interrogation, and this was every second night it was going on and also it was always at night time it was never in daytime, and of course she was working in the fields weeding the turnips.

“And the questions they were asking, things that can be asked in day time what correspondence they kept before the war, it was stupid, silly questions.”

Another’s mother was arrested for feeding porridge to a prisoner.

“She was arrested for that, she was taken to prison so seven of us left alone, so the eldest sister looked after us, she had to work and my second sister the same, and then it was a few months before the Red Cross heard of us, that we are alone, nobody to look after us and that’s how we were taken to the orphanage.”

Another remembers the brutality of working in the fields.

“One day my mother came back from the fields where she was working with blood gushing down her face, she had said something to the supervisor in the fields and he just took a rake to her. If we didn’t work, or couldn’t work, or rather if my parents couldn’t work we were not fed.”

After Germany invaded Russia in 1941, the Polish men who were in these collective farms in Siberia were taken away to fight the Germans, and the remaining women and children began an epic journey in stages south from the Siberian tundra, down through central Asia to Persia (Iran), many died from starvation or disease on the way.

Eventually the Red Cross became aware of their plight and a Polish diplomat convinced New Zealand’s Prime Minister Peter Fraser to accept around 800 of the stranded children, who by now were almost all orphans.

Krystyna Skwarkow was one of the few children who was still with her mother. As one of the few surviving adults she was the leader of a large group of the children. They travelled from Persia by train to India to catch a ship to New Zealand. She recalls the first Kiwis they met made a good impression on the children.

“When we arrived in Bombay, we told to board a ship, an American semi-war ship and on that ship were about 3000 New Zealand soldiers who were coming back from Cairo to New Zealand for a holiday or leave or something.

“There were 3000 of them and you know I think probably this part will remain in many minds of these children as perhaps the most remarkable event of the whole trip from Poland to New Zealand. And this is due mainly to the fact of how those soldiers behaved towards us.

“I remember we used to be terribly sick on the ship because we weren’t used to the sea travel and those soldiers, those New Zealand soldiers, would give us their own rations of fresh fruit and fresh greens because they wanted to help us.

“Now for them it was a tremendous sacrifice, because the heat on the ship was something unbelievable, and yet they were prepared to give us whatever they had; all they had.

“They looked after the boys especially. Remember those boys went through a tremendously hard life in Russia, very often they had to rob other people, steal even kill to get some bread for their family.

"They entertained us, they taught us haka, they taught us simple songs in English and they took over looking after the boys.

“And I think that our introduction to New Zealand, that first introduction to the New Zealand soldiers coming back to New Zealand with us was perhaps the good omen of what our life would be like in New Zealand later on.”

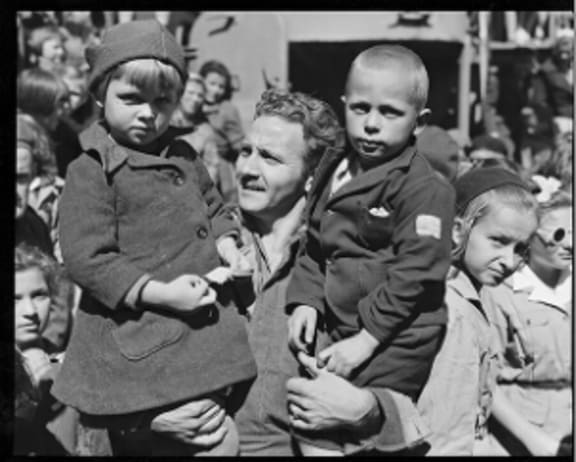

The ship carrying the 800 Polish children arrived in New Zealand on 1 November, 1944. They were greeted by Prime Minister Peter Fraser, and then travelled by train to Pahīatua in northern Wairarapa.

Their terrible story had been publicised in newspapers here and people took them to their hearts.

The children were treated as celebrities, with hundreds of people turning out at stations along the way to give them flowers and gifts and welcome them to New Zealand.

But as Krystyna remembered, the trauma they had been through meant it took some time for the children to adjust to a new life in the camp where regular meals could be taken for granted.

“When we came to the dining room the tables were laden with food, there was plenty of bread and plenty of meat and plenty of vegetables and there were New Zealand soldiers serving us at the table to start off with.

“And suddenly they noticed that the bread was going, disappearing, nothing else but just the bread, nobody was eating the bread, but it was just disappearing. They stole the bread from the dining room to hide it under the mattress because they couldn’t believe that they would have enough bread tomorrow.

“It took the children about 3 months not to steal bread and hide it under the mattress.

The soldiers seeing this broke down, they actually cried, wept, to see kids afraid that this bread they had been given today they couldn’t believe it would be there tomorrow.”

In 1944, after they arrived, the children became mini-celebrities and a few months later, in May 1945 they were invited to Wellington to help celebrate Poland’s national day. There was a Mass at the Catholic cathedral and a concert in the Town Hall, which was broadcast live across New Zealand on the radio.

Listen to a Spectrum radio documentary about their arrival in New Zealand: Will there Be Bread Tomorrow?