Everyone wants to know how bad our Omicron outbreak might get - and when. But experts running the numbers on that have copped flak in the media when scenarios they’ve been told to scope don't pan out. Meanwhile, media pundits who’ve been wrong in the past don't hold back on predicting the future.

Photo: photo / RNZ Mediawatch

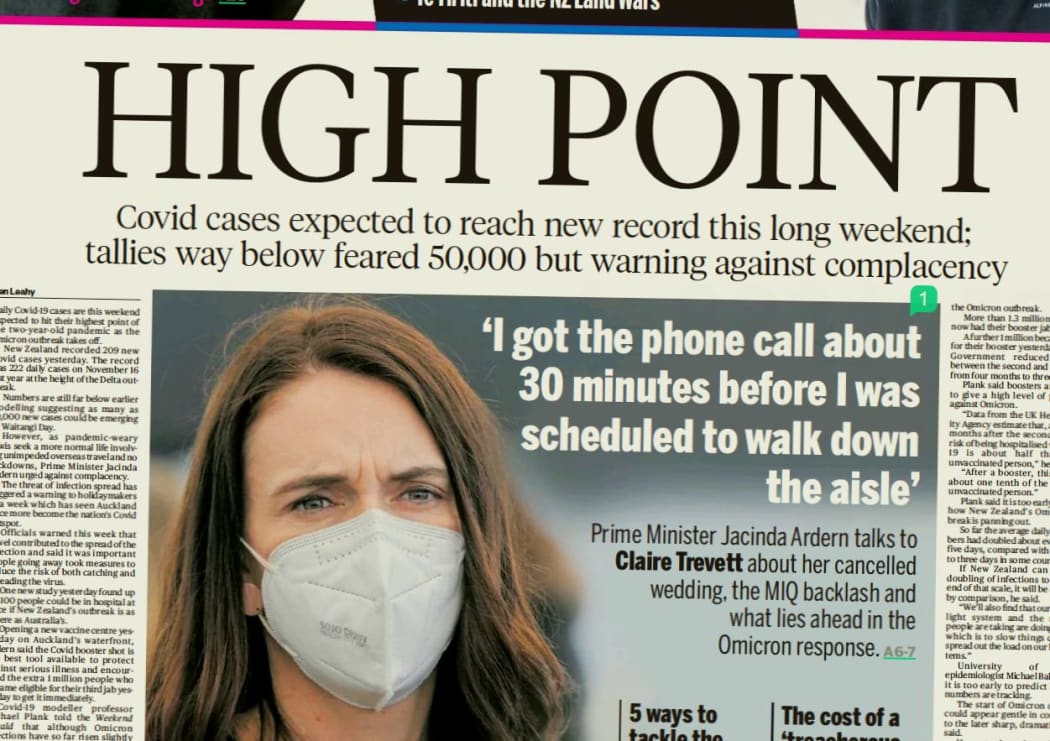

Professor Kurt Krause, University of Otago. Photo: Alan Dove Photography

About halfway through his recent explainer on the potential path of our Omicron outbreak, Stuff’s Keith Lynch records a note of uncertainty from one of the experts he’s interviewing.

“One of the experts I spoke to for this piece was humble enough to proactively tell me how often they’d been wrong about Covid,” the piece reads.

That expert, the infectious diseases physician and professor of biochemistry Kurt Krause, is hardly alone in having gummed up a few pandemic predictions.

Covid-19 has been accompanied by a twin outbreak of takes, many of which have turned out to be wildly off-base.

Krause is only really unusual in acknowledging he’s made mistakes.

Many of our prominent media commentators have shown little hint of that self-reflection, despite a series of head-scratching Covid-19 predictions.

In March 2020, Newstalk ZB host Martin Devlin told a caller he doesn’t believe Covid-19 “is a pandemic”.

The last two years would suggest that belief was incorrect.

Devlin wasn’t alone in downplaying the severity of the virus.

A month or two earlier, Nigel Latta had been urging people to “calm the hell down about coronavirus”, and reminding them the flu kills something like 500 people a year.

This vein of commentary is experiencing a renaissance with the emergence of Omicron.

On 1 February, NZME’s Barry Soper compared that variant to a bad cold, despite the fact the common cold is non-lethal, with rare exceptions, while at the time Omicron was killing more than 2000 people per day in the US. Covid-19 has now killed nearly 6 million people worldwide.

Other commentators have been off-target in their analysis of our Covid-19 response.

Former finance minister Steven Joyce appeared on NZME’s Leighton Smith Podcast in April 2020 to call elimination a “pie in the sky” fantasy.

New Zealand recorded its first zero Covid-19 day about two weeks after his comments, and had no active cases a month-and-a-half later.

More recently, Newstalk’s breakfast host Mike Hosking delivered a pessimistic forecast on the vaccine rollout, saying the country could hit a “wall of resistance” at around 78 percent vaccinated.

That wall of resistance turned out to be pretty flimsy, with 93 percent of the 12+ population now fully vaccinated.

It’s easy to criticise these predictions with the benefit of hindsight, but it’s not hard to make a wrong call on a shapeshifting pandemic, and several prominent experts have also proffered opinions they likely regret.

In January 2020, Director General of Health Ashley Bloomfield told reporters face masks are “not really any protection” from the virus.

Two months later, the virologist Siouxsie Wiles wrote an article reminding people that Covid-19 isn’t airborne.

In both cases, science has since moved on, and those experts have amended their positions.

Krause, the expert who made that stark admission of error to Lynch, says good science means acknowledging when you’re wrong and revising prior assumptions in light of new evidence.

He’d like to see those practices more often in the media.

“Maybe we need a stocktake at certain times during events like this to say ‘here’s what we know now, here’s what we thought was right and is wrong now, and here’s where we’re headed’. That would be refreshing. It would be refreshing if both sides acknowledged that and moved forward.”

Those sorts of admissions of ambiguity and uncertainty are at odds with a media ecosystem where the most strident takes are rewarded with a flood of algorithmically generated clicks.

Krause admits the media’s incentives often run counter to what he considers good scientific practice.

“I can see the importance of having the story be gripping and dramatic and on-point, and I don’t know how to handle that. A lot of science is kind of boring and plodding and that’s the beautiful thing about it - that it gets there in the end.”

Even so, he suggests commentators, reporters and public-facing experts pause occasionally to reflect on the things they’ve got wrong in the past, what they’re certain of in the present, and what they’re still learning about the pandemic.

“Maybe people would respond positively to that, because that’s kind of how science works.”