Australian soil scientist Alisa Bryce describes soil as a wonderful mysterious world, an underground jungle, a nexus of a portal between life and death.

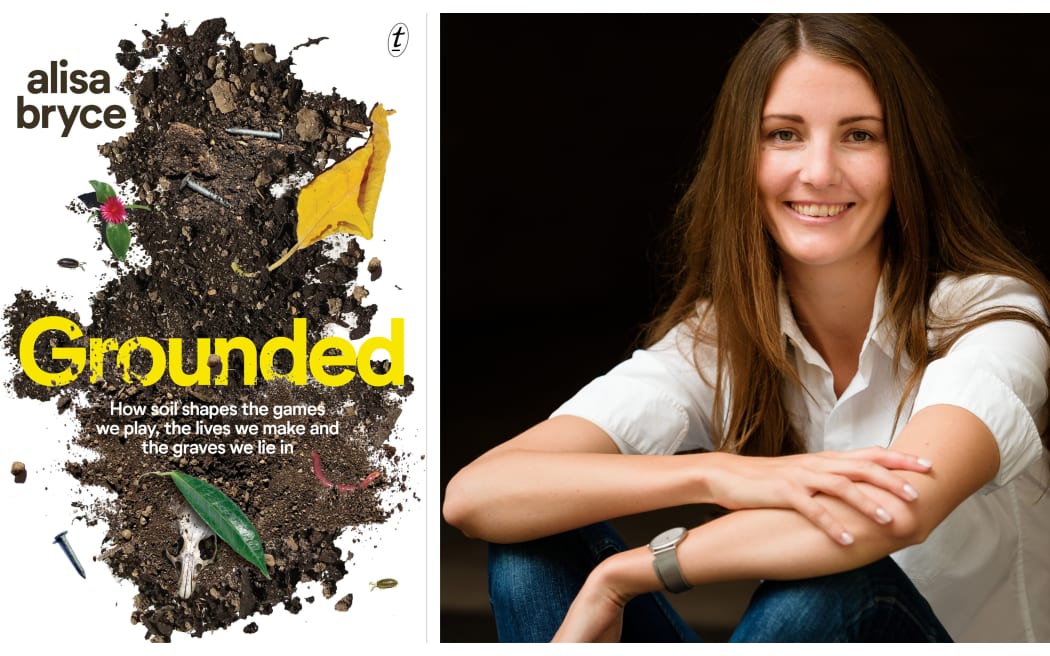

Alisa Bryce Photo: supplied by Text Publishing

In her popular science book, Grounded she focuses on how life could not exist without soil and how it informs so much of what we do, so much beyond agriculture.

She tells Nine to Noon the role of a soil scientist varies, but at the core the job is exciting and full of mysteries to be solved.

“We dig a lot of holes and there’s lots of variety on what a soil scientist can do," she says.

"Many work in agriculture, helping farmer improve crop growth. Quite a few help map the soil, because even though soil is everywhere and our understanding of it is pretty poor and we don’t have maps of it yet.”

Bryce choose to become an urban soil scientist, helping to beautify cities with flourishing parks and gardens, sports parks.

She is enthralled by the potential of soil, being full of microbes and nutrients, and the fact we don’t know 90 percent of what’s down there underground.

“That could hold the next wonder drug. There’s been some amazing research lately where there could be a replacement of morphine, that was found on some marine mud on the edge of a boat ramp," she says.

Professor Rob Capon, from University of Queensland's Institute for Molecular Bioscience, in 2019 announced his team were investigating the chemistry of marine fungi, including a 16-year-old sample collected next to a boat ramp in Tasmania.

“It is a magical substance of which we are totally dependent, she says.

Soil is the foundation of life, a precious resource, and for Bryce a lot of the narrative about soil today is negative, she says. It is ‘dirty’, full of germs, or the soil itself is prone to degradation.

“I want people to be excited about the soil and to realise that it is fun, it is interesting," she says. "It is part of our lives in this really great way, and that maybe by extension people will get excited and interested and we might get some more land care from a positive angle rather than just make people feel bad about something they may not have ever thought about before.”

Soil has a memory and it records life, and can point to moments of history even though there exists no physical evidence as in archeology, she says in the book.

“Soil itself can give you a great understanding if you know how to look and that can mean looking at the soil chemistry," she says.

“In Sydney, where the museum of Sydney now stands was going to be office blocks and it’s not, because of what the chemistry was saying. The bi-centenary was coming up and history was a very popular topic at the time and what the government wanted to understand was, was this an untouched site, or has something happened here historically that we just don’t know about.

“The soil scientist called Roy was doing some soil tests and the main thing he found was, even though the soil looked untouched, but when he tested the chemistry the PH was at 9 whereas usually it would be at 4.

“What this meant was this site was next to the very first government house and firewood was the main source of fuel, but over time everyone had emptied the buckets of ash out into the ground and effective they had over hundreds of years limed the soil.”

Soil has an impact on the flavour and quality of produce and after speaking to growers and winemakers and researching, she concluded that soil affects the taste of grapes.

“A pinot on one side of the hill can taste different to a pinot on the other side," she says.

"A talented trained wine maker can taste those differences, but there’s this big gaping hole of scientific knowledge. We don’t know all the flavour compounds, what’s happening in the soil to make these compounds in the grapes. So, it’s very exciting as there’s a lot to learn.”

Photo: Sippakorn Yamkasikorn/Pexels

Soil composition is important in sports parks and facilities too. Sports are often played on highly engineered soil.

“One reason I like being an urban soil scientist is that you can engineer soil, you can create it – design a recipe and manufacture something to meet your needs," Bryce says.

"If you had a pick under a high-end sports field you’re not seeing good rich black soil that you’d expect in a garden or paddock.

“It is probably 90-to-95 percent sand, specifically designed that way to cope with the amount of foot traffic and having really good drainage. The ground keepers have a challenging job keeping that grass alive growing on what is effectively beach sand.”

Cricket grounds on the other hand are usually on clay, as the pitch has to be fast and hard.

Microbes in soil offer the possibility of major advances in medicine too, she says.

“The general estimates are 90-to-95 percent we haven’t characterised in terms of microbes. So they say there’s more than billions and billions of microbes in one teaspoon of soil and we don’t know much of what’s there.

"One way our researchers are looking to find out what could be helpful is that they look for what microbe is beating up on another microbe.

"So they take a sample of soil and they get the microbes and they put them in a petri dish for example and little blobs grow and let’s say if there’s a white blob and a black blob and then the black blob is excreting something and the white blog is peeling away, almost like it’s shying away... that black blob is excreting something that might be useful to turn into a medicine antibiotic and that’s what Rob Capon from the University of Queensland is doing, that’s his methodology,” she says.

Ascertaining soil composition has been at times vital in modern warfare.

Before the Normandy landing, the allied forces spent a year working out nature of the soil. It involved sending in covert soil samplers in 1943 and bringing the samples back to England to work out whether the allied tanks would get suck in the mud.

In Vietnam tunnels played a crucial part in guerilla warfare against US. The tunnels were dug within alluvial soils with lots of iron oxide, which meant they set really hard.

“This tunnels where so strong that they could even withstand 16kg of charge, bombs from above," Bryce says.

Soil plays a huge role in police forensics. Bryce uses an example of a man being arrested in Australia over the murder of a number of people after being caught with blood and soil stained shovels in his car.

"Rob Fitzpatrick, the soil scientist, studied the soil on the shovel and looked at the colour and minerals, yellowish-pink colour, acidic, no salt. He helped narrow down area where women may have been buried. The soil had no organic matter, roots you’d expect in the top soil.

“Putting all these clues together he narrowed the search area down for the police to quarry. Only a few kilometres from the suspect’s house. Three weeks later they found a hand sticking out of the mud.”

Bryce discusses the effect our going back to the earth after death has on the land, concluding that modern burials have a negative impact.

Grassy cemeteries aren’t eco-friendly, as herbicides are used to maintain these, while coffins' glues and acids leach into the soil. Cremation releases a lot of CO2, while spreading ashes can put too much phosphorus and calcium into the soil.

“If too many people shatter ashes in the one place it changes the chemistry and weeds can grow," she says.

There are eco-alternatives becoming now more acceptable, including 'human composting' – a process where the decaying human being makes a lot of useful rich compost used to reclaim land.

Natural burials with a shroud and not coffin are being used in some areas as a means of rehabilitating the land, with no development on that land allowed. In Australia, for example, people are looking for degraded land to use in this capacity, returning humans to be earth and returning the earth to healthy protected space.